Learn the slang that peppers Bilibili’s “bullet curtain”

Watch the latest TV drama on Chinese video streaming site Bilibili, and you’ll be met with a barrage of “bullets” flying across the screen. Don’t worry, these projectiles can’t hurt you, though they could ruin (or enhance) your viewing experience.

For the many millions who spend hours every day on Bilibili, or “B Site (B站),” these flying comments are part of the fun of watching, and so ingrained that they sometimes imagine “a flock of bullet curtains are floating through my mind (现在,我脑海中一连串弹幕飘过 xiànzài, wǒ nǎohǎizhōng yìliánchuàn dànmù piāoguò)” in life away from their smart phone screen. The phrase describes when one has a lot to say or comment, and originates from the “bullet curtain (弹幕 dànmù)” on video streaming platforms, a feature that allows viewers to write comments which travel across the video while it is playing. Originating from Japan, the bullet curtain is one of Bilibili’s most loved features, and was what originally set it apart from other Chinese streaming platforms (until they all copied it).

The bullet curtain has become a review platform, discussion forum, and spoiler factory all in one. Commenters have developed their own stock phrases and expressions to express their surprise, pleasure, or disgust at what they see onscreen.

When a touching, thrilling, or unexpected moment in the plot occurs, viewers will warn of: “High energy ahead (前方高能 Qiánfāng gāonéng),” or even comment “High nuclear energy alert; noncombatants please evacuate (前方核能, 非战斗人员请撤离 Qiánfāng hénéng, fēi zhàndòu rényuán qǐng chèlí).” Netizens used the term to warn later viewers to be mentally prepared for stunning plot lines ahead, and the explosive numbers of “bullets” that will be flying across the screen.

As its name indicates, the bullet curtain can also be used to cover up scenes that audiences are reluctant to see. Commenters often band together to send countless messages saying “bullet curtain shield (弹幕护体 dànmù hùtǐ),” in order to envelop scenes that are too intimidating to watch, such as when a hero dies. Viewers also provide alerts for future watchers to prepare when there is a loud noise or jump-scare approaching: “Pay attention to your volume (音量注意 Yīnliàng zhùyì).”

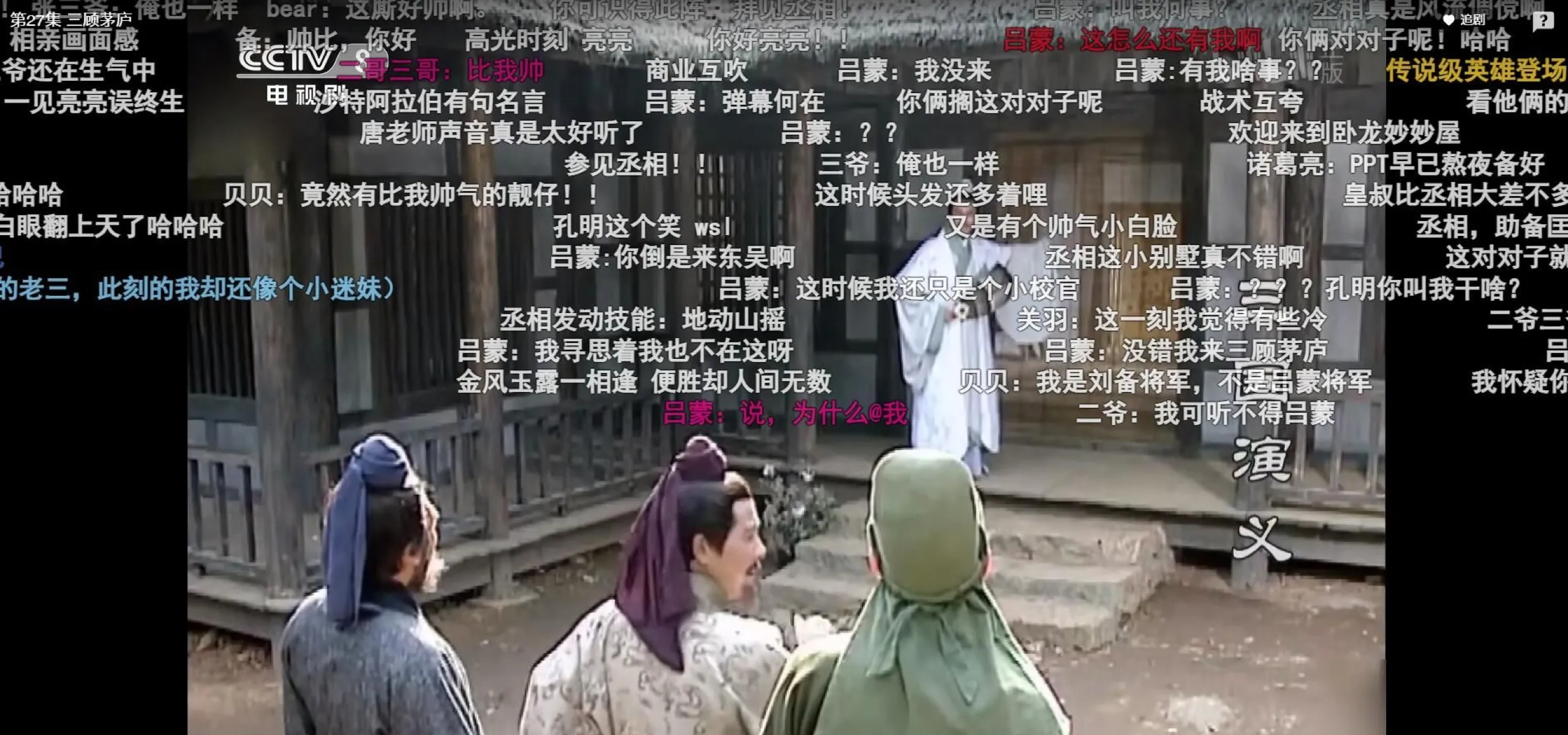

Famous or long-awaited scenes, such as when the protagonists enjoy their first kiss or a king finally wins back his throne, are met with a barrage of bullets reading: “Famous scenes alert (名场面预警 Míng chǎngmiàn yùjǐng).” In the 1994 TV adaptation of Romance of the Three Kingdoms (《三国演义》), nicknamed the “treasure of Bilibili (镇站之宝 zhènzhàn zhī bǎo),” when the warlord Liu Bei (刘备) goes to recruit the statesman and military genius Zhuge Liang (诸葛亮), it’s almost impossible to see the action due to all the comments flying across this famous scene that every schoolchild knows.

On the other hand, awkward scenes where the protagonist endures “social death” attract a different warning: “Dark and embarrassing scenes alert (冥场面预警 Míng chǎngmiàn yùjǐng),” where viewers switch the homophone 名 (míng, famous) in “famous scene” with 冥 (míng, the nether world).

When characters speak their most famous lines, audiences pepper the screen with calls to “take photos with the famous lines (名句合影 míngjù héyǐng),” as a mark that they were there for this historic moment. When Zhuge Liang says to the politician Wang Lang, “I have never seen such a shameless man (我从未见过有如此厚颜无耻之人 Wǒ cóngwèi jiànguò yǒu rúcǐ hòuyán wúchǐ zhī rén)” the screen explodes with comments like “Everyone, please stand up (全体起立 Quántǐ qǐlì),” and “Recite the whole thing (全文背诵 Quánwén bèisòng).”

The bullet curtain is also a space for expressing ones feelings about the onscreen action. Toward the end of episodes that audiences are loath to see conclude, viewers express their dismay by commenting “lonely (寂寞 jìmò),” or “lonely in advance (提前寂寞 tíqián jìmò).” They even try to coax the progress bar to grow a little longer, hoping the episode never ends: “You are a mature progress bar, and you need to grow up a bit longer by yourself (你是一个成熟的进度条了,你需要自己长大 Nǐ shì yí gè chéngshú de jìndùtiáo le, nǐ xūyào zìjǐ zhǎngdà).”

Eventually, though, the video must conclude, and viewers bid farewell to their fellow screen addicts: “See you next episode, my friends (下集见,朋友们 Xiàjí jiàn, péngyoumen).” Or “See you in seven years (七年后见 qīnián hòu jiàn),” since many anime shows release a new episode only once a week, with each day feeling like a whole year (度日如年 dùrì rúnián) to superfans. At the end of the whole season, they post, “Scatter flowers at the end (完结撒花 wánjié sǎhuā)” as a mark of celebration and respect for the show’s creators.

For shows that are not yet widely popular, viewers will “火钳刘明 (huǒqián liúmíng),” a play on “火前留名 (huǒ qián liúmíng, “leave my name before it’s hot”) as a way of claiming they were fans before it was cool.

The bullet curtain has been a feature of online streaming platforms for years, with the language of the bullet comments even entering everyday speech for young Chinese. Of course, not everyone is happy with the spoilers, or having key scenes blocked by words flying across the screen. These people might have different favorite feature on Bilibili—a button below the video they can click to “turn off the bullet curtain (关闭弹幕 guānbì dànmù).”