Regional ‘new’ cities vie for graduates with cushy offers, but will the ‘talent war’ end in tiers?

To stay or leave—it’s the question many in China’s first-tier cities are asking. Faced with skyrocketing housing prices, rising expenses, and increasingly fierce competition for jobs, those living in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen are considering alternative options.

Traditionally, though, there haven’t been many: Most second- and third-tier cities lack promising work opportunities, entertainment, and nightlife associated with a modern city, and the well-developed infrastructure to woo the middle class away. On social media, the dilemma has been skewered in a world-weary viral phrase: “The first-tier cities cannot accommodate my body, while the lower tier cities cannot fill my soul.”

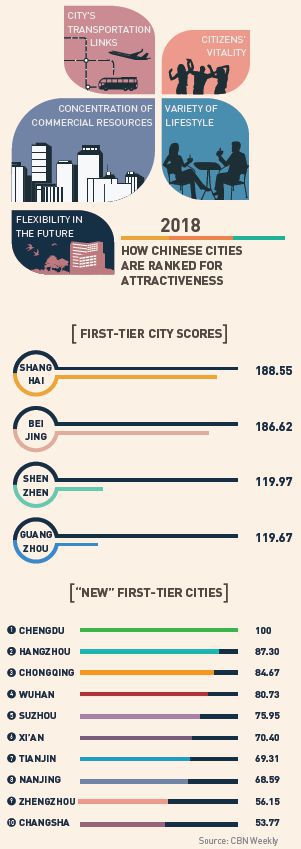

Enter the “New First-Tier Cities”—as coined by CBN Weekly in 2013—hoping to solve the problem. Every year, the magazine ranks hundreds of Chinese cities’ commercial attractions based on five indicators—concentration of commercial resources, transport links, the “vitality” of citizens, variety of lifestyle, and “flexibility toward the future.” Those in the “new first-tier” category—which is positioned between China’s four first-tier cities (Beijing, Shenzhen, Shanghai, and Guangzhou) and 30 second-tier cites—are aiming to be the next locus and engine of China’s urban growth.

According to CBN’s latest rankings, Chengdu, the capital of southwest China’s Sichuan province, is the highest-ranked among the 15 New First-Tier Cities, followed by Hangzhou, Chongqing, Wuhan, Suzhou, and Xi’an. Marketing professional Yang Hao, a 30-something who moved to Chengdu from Beijing in 2012, says he’s not surprised. “Chengdu is developing very rapidly,” Yang tells TWOC, “So much has already changed since I first got here.”

In June 2012, Yang was sent on a business trip to Chengdu, where he enjoyed the relaxed pace of life, a far cry from his hectic life in the capital (during which he changed jobs three times in five years). Yang likens Beijing to “a huge machine. Living there, you cannot have your own shape; you can only be forged into whatever shape it needs.”

By contrast, he felt that people living in Chengdu do not seem as anxious about the future. “There’s just a feeling that no one is going to shove you in the subway.”

When his company offered him a new position in Chengdu, Yang accepted it with little hesitation. Though he wouldn’t say he was “fleeing” Beijing, Yang recalls never really having a sense of belonging in the city. “In Beijing, almost every day I heard people mention the term ‘外地人’ (“outsider,” those without a Beijing household registration, or anyone not born and raised in the city)!” “But I have never once heard that phrase in Chengdu.”

On a clear day in Chengdu, residents organize an impromptu tea house in Wangjiang Park

Not only does Chengdu seem more open to outsiders, but the local government has ambitions to attract more to the city. In 2017, the “Plan for Migrants in Chengdu,” was released, allowing people with a bachelor’s degree or above, who have committed to working at least two years for a local company, to apply for a Chengdu registration, or hukou. The city even set up 20 special hostels, providing seven days’ free accommodation for job-seekers.

Yang marvels at how Chengdu has changed over the last five years. “Following the development process of Beijing. It is expanding from a First Ring [Road] and a Second Ring all the way to a Fifth Ring.” He admits, though, that the western city still has a long way to catch up with first-tier metropolises. Exciting opportunities are not as easy to come by—especially for his Korean wife. In Beijing, she found camaraderie in Wangjing’s Korea Town, as well as a plethora of work opportunities.

Yet in spite of minor setbacks, Yang and his wife now plan to piggyback on the rise of Chengdu to the very top. “Chengdu is changing…The city recognized that its future development depends on attracting people, or talent.”

“What’s the most expensive thing in the 21st century?” asked the villain in Feng Xiaogang’s 2004 movie, A World Without Thieves. “Talent!” Fourteen years later, its prophecy has come true. Since 2017, dozens of cities, including several “New First-Tier Cities,” have rolled out favorable policies to attract graduates—a “talent-grab war,” in the words of Chinese media.

Though each cities’ policies vary, they generally focus on issues such as hukou and housing subsidies. In 2017, Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province, permitted university graduates to buy and rent at prices 20 percent lower than market rates. That same year, Changsha, capital of Hunan, announced that it would offer housing and living subsidies between 6,000 RMB to 15,000 RMB per year for graduates with degrees that could contribute to the city’s development.

And in Jiangsu province’s capital, Nanjing, holders of bachelor or vocational degrees, overseas returnees, and self-employed graduates were invited to apply for 30-square-meter public rental houses or subsidies between 600 RMB to 1,000 RMB per month.

“In the short term, these policies, like housing subsidies, are attractive, especially in cities with a large amount of universities, like Wuhan and Xi’an,” Li Yan, leader of 58 Recruitment Academy, told 21st Century Business Herald.

Tianjin, a municipality near Beijing, upped the ante earlier this year by offering a hukou for anyone under 40 with a bachelor’s degree, or under 45 with a master’s degree, and all who have a PhD; less than 24 hours after the announcement, the municipality was besieged by over 300,000 applications on its app. In 2017, over 142,000 graduates registered their hukou in Wuhan, six times that of 2016, according to Guangming Daily; 245,000 people transferred their hukou to Xi’an; and Changsha saw a registered population increase of about 273,000.

In May, a survey carried out by Zhaopin.com, one of China’s leading recruitment websites, suggested over 40 percent of graduates in 2018 wanted to work in six of the major New First-Tier Cities—Hangzhou, Chengdu, Chongqing, Tianjin, Nanjing, and Wuhan; about 34 percent had already signed a contract.

Among these cities, Hangzhou is widely considered the most attractive: According to a report from recruitment website Boss Zhipin, nearly 90 percent of graduates from universities in Hangzhou chose to stay after graduation. For every 100 who leave, it’s estimated there are 132 graduates settling, a ratio comfortably ahead of other first-tier cities. Hangzhou is also the most popular city among overseas returnees, even outperforming Beijing and Shanghai, according to a report from LinkedIn in 2017.

Alibaba’s Hangzhou headquarters is known for its sleek campus and long hours for IT workers

For many, the charms of Hangzhou are as obvious as the old saying suggests: “There’s heaven in the sky, and Suzhou and Hangzhou on Earth.” For job-seekers, though, it’s Alibaba, and other companies headquartered in Hangzhou’s well-developed tech sector, that are the key to this “paradise.”

The reason Li Jing (pseudonym) moved from Beijing to Hangzhou was the opportunity to work for the e-commerce giant. When her company was acquired by Alibaba in 2015, the product developer immediately accepted the offer of a new contract. “For me, it was just an opportunity to work in a bigger platform to continue developing my product,” says Li. “But my parents were very glad I came to Hangzhou, because they were concerned with Beijing’s housing prices.”

Alibaba’s presence has given Hangzhou the nickname “Capital of E-commerce,” and Qdaily reported that over 36 percent of rentals in the city were to IT workers. But while many hope that life in the New First-Tier Cities will be less chaotic and more fulfilling than the old first-tiers, Li’s experience suggests this is not necessarily true. She believes her life in Hangzhou is more stressful, even though she earns five times her Beijing salary. “Every weekday, I leave home at 9 a.m. and arrive home at 10 p.m. I also work overtime at weekends.”

“In my free time, I need to improve myself,” she adds. “In this industry, if you want to catch up with others, you have to work really hard.” Li says that current policies are far from enough—high-end, experienced workers are still in short supply. “I never heard of any department in Alibaba without vacancies.”

Others disagree. Lu Ming, a scholar from Shanghai Jiao Tong University, believes the policies are intrinsically unfair. “All of these talent-grabbing policies are just using taxpayers’ money to subsidize university graduates, who already have the potential to earn high incomes,” Lu told the 21st Century Business Herald. “It is not right if cities only try to keep students, while those without a diploma are forced to leave because they cannot access the same public welfare.”

Zhang Shuguang, deputy director at the Unirule Institute of Economics, believes that talent-grabbing policies are generally good. “We used to not respect talent,” he noted at the 2018 China’s Economic Growth and Cycles Summit. However, Zhang warned that there are problems with “the standard that defines a high-end talent, and the settlement packages…On the one hand, we see governments are attracting high-end talents; on the other hand, we also see some local governments evicting low-end labor.”

“Talent is multi-faceted,” said Zhang. “Without free movement of people, I think such policies won’t produce satisfactory outcomes.”

There’s also the question of whether the influx into these New First-Tier Cities is sustainable: While Yang felt that one can really “have a life” outside work in Chengdu, Li, in Hangzhou, feels it may soon be time to leave. Although she has already married and bought two apartments in the city, “I can see the ‘ceiling’ of my career, and if [so]…I don’t want to invest all my time and energy on it,” Li says, explaining that she feels it is “the right time” to leave. “Many friends feel I can just continue working at Alibaba for the rest of my life, but they don’t realize how exhausting that is.”

Days after she spoke with TWOC, Li updated her WeChat Moments, announcing that she has quit. She’s planning to relocate, perhaps even go abroad to New Zealand. “I do not want to settle down in any specific place now,” she tells TWOC, adding perhaps the most significant factor in these decisions, “I think the internet has reduced the regional influence on people’s lives.”

Shock of the New is a story from our issue, “Modern Family.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the App Store.