Millennials now comprise the majority of China’s migrant workers—from our cover story

It was five days before Spring Festival, but at one Beijing chain restaurant, a whole section of the staff was nowhere to be found. “The ‘post-90s’ workers have all gone home—only post-70s and post-80s ‘aunties’ will work during the holidays,” the cashier, a woman in her 30s, explained self-deprecatingly.

Not every demographic hankers after an apartment in a first-tier city or international travel. But for China’s jiulinghou workers, the “generation gap” is not just a first-world problem. “My parents are farmers…all they want for me is to learn a trade, get a 9-to-5 job in the local prefectural city, and visit home a few times a week,” scoffs Wang Qunhong, a 28-year-old Ningbo saleswoman originally from Jiangxi province. “I preferred to do something with more money and more freedom.”

The stereotypes can cut both ways. Song Yi, documentary filmmaker on Beijing’s post-90s migrant workers, says the group faces the same condemnations as middle class millennials: “Old workers say young workers can’t ‘eat bitterness.’”

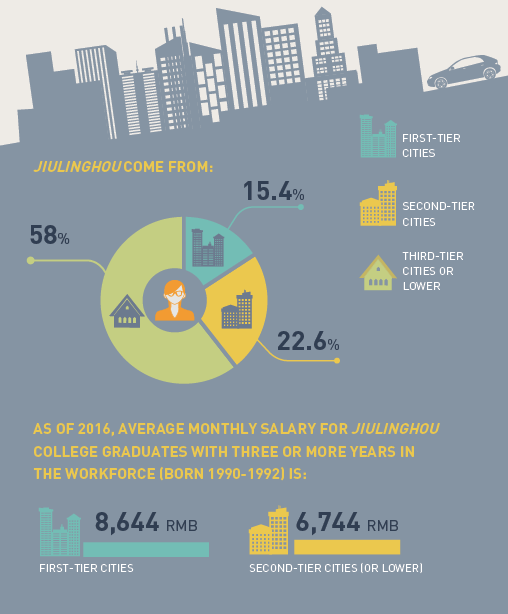

“[The older generation’s] views don’t match reality,” Wang retorts. Like everything in China, the economic prospects for China’s internal migrants have changed dramatically since the 1980s, when the first rural workers began to arrive in factories and construction sites after Deng Xiaoping’s market reforms. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, individuals born after the 1980s are becoming China’s primary blue-collar workforce, comprising 49.7 percent of the country’s total 2.8 million rural migrant workers as of 2016. Unofficial studies have put the figure as high as 80 percent in cities, like Ningbo.

A joint study by the city’s migrant labor office and Academy of Social Sciences estimates that around 18 percent of Ningbo’s migrant workers are jiulinghou. They congregate disproportionately in the low end of the “tertiary sector”—82.2 are involved in the retail, hospitality, and assorted service jobs—as opportunities shrink in manufacturing and construction, go-to occupations of the previous generation. Compared to these traditional blue-collar sectors, though, wages in the service industry have stagnated.

China’s jiulinghou migrants remain unfazed. In the Ningbo study, workers chose “expanding one’s horizons” (22.5 percent) and “liking city life” (21.2 percent) as their top reasons for migrating, with few putting money first. Employers who were surveyed characterize their jiulinghou workers as higher educated on average—that is, have attended high school—and more demanding of advancement, fair wages, and better working conditions. “Jiulinghou Job-Seekers Require WiFi in the Dorms,” declared a headline of Guangzhou Daily after reporters visited a local job fair.

Wang says it was a combination of boredom and financial need that took her to Beijing and later Ningbo at age 19, after finishing trade school to please her parents. “I felt like I should go ‘out there’ and challenge myself,” she says. She cycled through various jobs, from nursing attendant to supermarket owner, before discovering one that met all her requirements. “I’m in sales now, and the pay is good, I get insurance, and my time is very flexible—there’s almost too much free time.”

Other jiulinghou see city life as strategic preparation for the future. At a Hangzhou job fair, People’s Daily interviewed a jiulinghou who was still jobless on his third visit, having turned down many offers including courier, computer repairs, and warehouse management. “I want to find something that will teach me a skill,” he told the reporter. Twenty-six-year-old Sun Wei, another trade school graduate from Shandong, chose a job in the cafeteria of a major Beijing university, telling TWOC, “I plan to learn English, and then take the IELTS.”

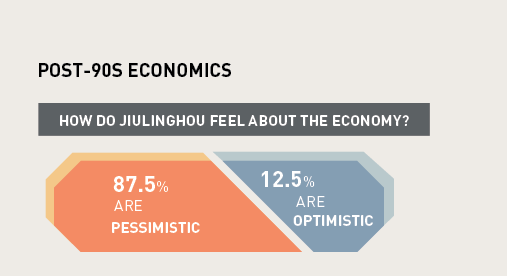

Song says that young workers are more aware than ever of their position in society. “Many are the second, even the third generation of workers in their family. They’ve grown up in the city, have never farmed, yet they’re still treated as outsiders,” he explains. “We call them ‘second-generation migrants.’” This became the title of one of his films, in which jiulinghou workers dramatized real-life incidents for the screen. In one scene, the protagonist hosts a large gathering of workers interested in starting an internet business, but as food is eaten and beer is drunk, they fall depressed one by one. “We don’t know how to do these things,” one character finally says.

This persistent generational disappointment is why, in 2014, a series of reports by the Communist Youth League and Peking University identified second-generation migrants as a potential threat to social stability. “Being better educated than the previous generation, growing up in the city, they are more conscious of social inequality,” Peking University professor Lu Huiling, co-author of the reports, explained to China Youth Daily. More resourceful and sophisticated than their elders, jiulinghou nevertheless share with them the burden of their rural hukou.

In the last scenes of Second Generation Migrant, the protagonist scales down his business dreams to open a courier office. “We chose to end with this service profession because it’s becoming what factory jobs were in the past, a symptom of our present economic development and its contradictions,” Song explained. “A lot of worker’s ‘class consciousness’ is going to start from there.” But as the credits roll, the heavy doors of the warehouse slams shut on the workers inside—the success or failure of our protagonists is literally impossible to tell.

The Noughty Nineties: The Worker is a story from our issue, “The Noughty Nineties.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the App Store.