Artist Liang Shaoji talks to TWOC about using the symbolism of silk to lay bare Earth’s evolution

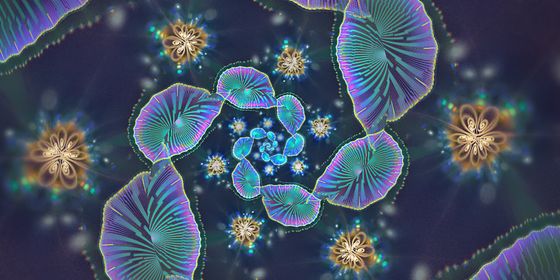

The glass case is lined by dozens of palm-sized miniature beds—but not the warm, supportive kind that invites a good night’s sleep. Rather, twisted together from charred copper coils the artist found in electronic repair shops in the 1990s, these bed frames look rugged and even feverish. Each is entangled with a wild web of silk and, occasionally, a cocoon that serves as both the occupant’s cradle and coffin.

Each bed, a vestige of the life and work of a silkworm, conjures up an image of its beginning: a naked worm squirming on naked wires, a creature very out of place, trying to make sense of the surroundings life has given it.

“Beds/Nature Series No.10” is just one thread that makes up “A Silky Entanglement,” a solo exhibition from interdisciplinary artist Liang Shaoji, curated by Hou Hanru, currently on view at the Power Station of Art in Shanghai. Liang’s work spans a variety of media and formats with one main theme: the life processes of silkworms, whom he calls his “collaborative partners.”

These partners have guided him to create “Beds/Nature Series No.10.” In the Shanghai-born artist’s work with silkworms in the early 1990s, he guarded them day and night. One night, Liang woke up on the floor to find a silkworm had fallen on him and spun a thin cocoon on his collar. He had an epiphany, “Consumed by the pursuits of life, am I not a silkworm myself?”

Combining this experience with the Daoist idea of qi wu (齐物), transcending above the differences of this world to find equality among all things, Liang arrived at the idea of “Beds”: We begin and end our lives on beds, while spending most of our living hours on them too. By subjugating silkworms, quite literally, to the same process of exhausting an entire life on a bed, Liang harvests a visual impression of a chaotic liveliness and distilled all that is beautiful and futile about existence.

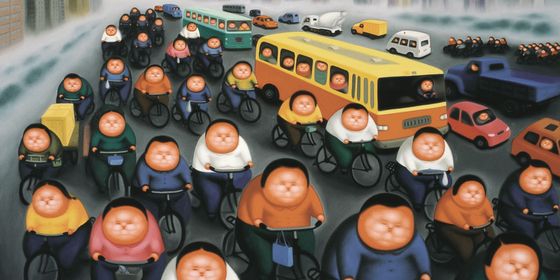

Silk became one of China’s chief exports in the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) and has been an internationally valued commodity since. However, Liang’s experiments with having silkworms produce silk on various surfaces and structures is a far cry from the material’s usual symbolism of luxury and oriental mystique in the West.

In Chinese culture, silk has spawned a plethora of metaphors, sometimes contradictory, about attitudes toward life. In an interview with news site The Paper about the current exhibition, Liang muses that on one hand, there is the Chinese saying, “The spring silkworm does not stop spewing silk until it dies (春蚕到死丝方尽),” in praise of silkworms’ spirit of devotion. On the other, there is “spin a cocoon around oneself (作茧自缚),” which mocks someone who is trapped in the consequences of their own doings. Liang relishes the creative tension born out of these paradoxes, which make silk intriguing as an artistic medium.

As some exhibited works are highly conceptual, and their descriptions are laden with cultural references to Daoism, Buddhism, and Western schools of thought, “A Silky Entanglement” sometimes risks being esoteric to audiences new to Liang’s works.

Life, Entangled: Artist Liang Shaoji on Working with Silkworms is a story from our issue, “Access Wanted.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the App Store.