With Big Beer looming, is China’s nascent craft-brewing scene facing its biggest threat yet?

It’s the Friday before Spring Festival and around 150 people are crammed into one of Beijing’s most popular brewpubs. The crowd is roughly a third white male “neck-beards,” the rest Chinese, sinking a few pints of 40 RMB ale before they spread across the country to visit relatives who will likely have never heard of craft beer, still less tried it.

I’m drinking an Edmund Backhouse pilsner, its name a nod to the tearaway expat scholar and fabulist, whose Qing-era sex memoir was to later scandalize historian Hugh Trevor-Roper. The young academic famously investigated Hitler’s death after the defeat of Nazi Germany—the very country that helped introduce modern brewing to China. It feels like there’s history in every sip; and maybe a few pints of Backhouse will lead to some similar adventures—or, at least, loosen my tongue enough to tell some tall tales of my own.

China may be only a decade into its craft beer revolution, but this movement—as some see it—was also initiated by foreign forces. Today there are over 300 craft breweries on the mainland, and the potential for growth is huge. Several of the largest overseas conglomerates are now circling these early pioneers, salivating at the potential for growth. Some local brewers see the chance to make a quick buck, but others view “Big Beer” as the first nail in the coffin for a localized small-batch approach that’s been struggling to establish itself.

Predictably, China already lays claim to one of the world’s oldest beers, a brew made in today’s Shaanxi province using fermented millet, pearl barley, and snake gourd root, allegedly dating back to the Neolithic Age. One Hong Kong brewery has even attempted to recreate the aged ale, describing it as “sweet, tart, and funky.”

Yet, up until about 10 years ago, its drinking culture was dominated by just a few variants of sorghum liquor (the infamous baijiu), Shaanxi-style yellow wine, and four tepid lager brands: Snow, Harbin, Yanjing, and Tsingtao. Almost unheard of outside China, these regional mega-brews take up almost 60 percent of the Chinese market, according to Euromonitor. Other than the occasional European beer hall—Paulaner Bräuhaus opened its first branch outside Germany, in Beijing, in 1992—China and the Big Four remained comfortably, robustly homebound.

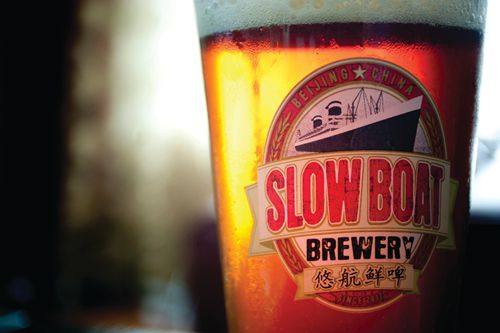

Slow Boat was one of the first brewpubs to open in Beijing, and now serves over a dozen varieties of beer (courtesy of Slow Boat)

Then came the Olympics in 2008. Quantities of craft ale—imported to satisfy an American appetite whetted by small-batch brewers from cities such as Portland, San Diego, and Denver—were simply left on supermarket shelves after the Games, a glut of good grog going to waste. “The craft beer just sat there forever…you were paying eight or nine bucks for beer that had expired and I was like, OK, I am done,” says Carl Setzer, who owns the Great Leap Brewery chain.

With piercing blue eyes, lumberjack beard, and a frame not dissimilar from one of his kegs, Setzer has been called China’s first proper craft brewer; certainly, he doesn’t argue the point. “There hasn’t been anyone able to do anything close to what we have done,” he says with a look of utter sincerity. Setzer is the no-nonsense, salty union-rep of China’s independent craft beer scene—if Big Beer wants a trade war, he’s seemingly happy to bring it.

In truth, a man by the name of Gao Yan had already set up a small brewpub in the southern city of Nanjing, under the Master Gao brand, and has been carving out a successful business ever since—but the foreign press corps, ever reluctant to leave the capital, seized on the opening of Setzer’s tiny taproom, established in a Beijing hutong in 2010 and still soldiering on, as the dawn of a new beer-a.

Setzer may have been first to market, but others had been nursing similar dreams around the same time. The majority had been amateur hobbyists back home—“just mucking around in a friend’s garage,” as one put it—who, frustrated by the lack of options, started experimenting for the hell of it.

“The import market was pretty weak, with only a few craft beers coming in, and they were often stale,” says Richard Ammerman, one the oldest employees of Jing-A, a taproom-brewpub in the capital. “There were quite a few craft beers I missed, so that’s how I got into it. It’s a lot of fun when you’re doing it at home. You have quite a lot more room to make mistakes…Worst-case scenario, your friends will drink anything.”

That’s no longer quite the case. The industry has kicked into gear. Though the big-city small brewers outwardly claim camaraderie, there is a fierce rivalry that often spills into outright hostility once the beers flow. While brewers keep their eyes peeled for new players on the market, they claim—publicly, perhaps disingenuously—the more, the merrier. It’s proof that there’s a strong market and brewers are more than just a clique of obsessive crazies.

“Great Leap preceded us by about half a year, which we had two thoughts about,” says Chandler Jurinka, a former military man who founded Slowboat Brewing Company in 2011, narrowly missing the title of “Beijing’s first craft brewery.” “It was like well, ‘Oh well, there is a new craft beer guy in the hutong…Now, as disappointing as it was that we were not the first, it was also invigorating because we realized we were not the only ones…it was a vindication of our business model.” This vanguard included Jing-A, which now has two locations in Beijing, along with NBeer, Panda, Peiping, Forever Beer, and Arrow Factory; KrakHaus Brewery in Huizhou, Tianjin’s WE Brewery, Hebei’s Urbrew, Taps in Shenzhen, Bad Monkey in Dali, PK and Liberty Brewing in Guangdong province, and Boxing Cat in Shanghai—the latter now the locus of some controversy.

In March 2017, Anheuser-Busch InBev, a Belgian-Brazilian beverage conglomerate and the world’s largest brewer, purchased Boxing Cat. The sum was undisclosed but, off the record, two sources said it was an initial figure of 10 million USD, with a further 30 million based on future sales. The figure is in line with the 39 million paid by the conglomerate for Goose Island, a Chicago-based brewer, in 2011.

Despite the Goose Island purchase, AB InBev missed the boat on the emergence of craft beer in America, apparently not realizing it would grow to around 15 percent of the market in less than two decades. Of the 6,000 craft brands in the US, AB InBev owns about 10; for a company that rakes in over 50 billion USD annually, and sells nearly one-third of the world’s ale, that’s pretty small beer.

Yet AB InBev seems determined not to make the same mistake again in China, which now has over 300 craft breweries, with brewers claiming an increase in annual sales of over 25 percent. Locals fear AB InBev’s aggressive business practices, and worry they are going to be cannibalized.

Another issue is chancers hoping to piggyback off a brewer’s hipster cachet by stealing it. Dali’s long-running Bad Monkey brewery has issued legal letters to at least eight imposters bearing the distinctive monkey logo and selling their own beer, branded as Bad Monkey.

“Those copycats are just unimaginative…” says 42-year-old co-owner Scott Williams, using a curseword commonly hurled by cabbies. “No ideas, no nothing. ’Course, it’s a bit flattering, because it hasn’t happened to Boxing Cat or anything.”

In theory, there should be room for everyone—after all, China is vast and varied, and its people love to drink. Chinese literature is littered with wives pawning gold hairpins to fund their husbands’ three-day benders, and its poets are as known for their alcoholism as their verse. Drinking to women, drinking to the gods, drinking to the moon, the Chinese seem happy to ganbei at the drop of a glass. Eighth-century poet Li Bai wrote obsessively about wine and drunkenness, and was known as one of the “Eight Immortals of the Wine,” a group of lauded Tang literati known for their love of liquor.

Modern drinking culture, though, is not what it was: Many youngsters loathe baijiu banquets—which often start early and continue until the boss is red-faced and needs to be wheeled out—and the culture of toasts and face is not well suited to the leisurely supping of craft brews. Younger, urban Chinese are gradually shunning this binge-booze culture, spurring the craft scene—though the latter makes up as little as 0.1 percent of the current market, according to Fortune. As one Beijing-based brewer put it, “The Yanjing brewing company made 7.4 million hectoliters last year; craft beer in China doesn’t even register as a percentage of the loss that they dump during packaging.”

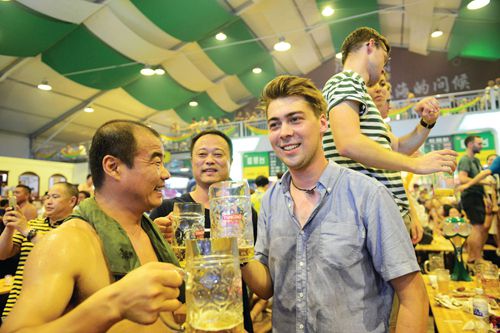

The Qingdao International Beer Festival is Tsingtao’s banner annual celebration, but some complain that it lacks international brands—and craft beer (VCG)

Word on the street is that, when AB InBev approached Great Leap’s Setzer, he literally told them to “f*ck off.” So I go to the horse’s mouth: “That’s not a rumor. That’s something that happened,” Setzer says with relish. “They didn’t come to me first, they came to everyone. They went to Shangri-La, they went to Jing-A [but] not everyone told them where to go…[almost] everybody else bent over backwards to try to get that cash, because—minus Boxing Cat—most of the craft breweries in China started after 2011. The only thing they know about craft beer is that, if you do it, you will get money. Someone will come and buy it from you.”

But Big Beer must also proceed cautiously: Boxing Cat’s first investment in Beijing, a pop-up aggressively positioned opposite Jing-A’s original taproom, was in a popular F&B courtyard that has already fallen to the relentless wrecking ball of development. Meanwhile, Setzer has been spending his own money to arrange public forums for leading brewers to discuss how AB InBev might be disrupting the global market. It’s a perfect pulpit for the big man to make his feelings explicitly known, but almost every brewer TWOC spoke to had concerns.

“I don’t think the big guys coming and taking over is great,” Jurinka says. “What it does is liken industrial beer to local beer. There is nothing wrong with taking a local beer and distributing all over China. But those are two different things. What we do is local; we sell to locals, the people employed are local.” Subsidies are another concern. “It is competing with a different war chest. They are giving away free beer. Their marketing budgets are hundreds of what ours are…I am a big believer that the best beer is the beer in front of you, but still.”

The founder of Arrow Factory Brewing, Will Yorke is a wiry Englishman and one of the more cerebral brewers in China, though when we meet he is carrying a box of freshly picked strawberries that he grinningly tells me he plans to mash up to make a keg. Our conversation takes in Germany’s beer purity laws, whether his role as brewer would be acceptable to Buddhist practice, and the ecological ethics of growing hops (they use a lot of water). He offers a thoughtful analysis of AB InBev’s entry.

“A lot of people feel that…it is very cynical. It’s not authentic. But then AB Inbev are not in the business to be authentic or anything else,” he argues. “The next problem is what AB InBev actually plan to do…they need to please the shareholders. They need to make money…I think they actually have a whole concept of disrupting the market. If they do intend to eradicate these small players, whose livelihoods and whose passion is brewing beer, then it is a very bad thing. It is not cool.”

Many say that Zx Ventures, the subsidiary of AB InBev in charge of craft acquisition in China, is intentionally setting out to do this. Feelings run high on the matter. “Zx Ventures are in charge of disrupting craft beer in the market…they own all of the AB InBev craft beer portfolio. And up until two months ago their website said, very clearly that their goal was to disrupt the international craft beer market,” scowls Setzer. “But really that was just them being honest for one minute, as they deleted it from the site.”

Zx Ventures did not respond to requests for comment, but admits on their site that “Zx Ventures is constantly assessing, testing, and investing in contemporary solutions and technologies that have the potential to disrupt our core business.” There is no doubt AB Inbev has the potential to grab a large market share: While it is relatively straightforward for a small brewery to open a taproom and retail their beer, finding a secure long-term lease is tricky—and when it comes to distributing wholesale, it is very difficult to sell beer nationwide.

A local reveler enjoys a flagon of lager with a foreign visitor during the Qingdao Festival in 2017 (VCG)

Chinese regulations state that, in order to get the relevant quality standard certificates, brewers need to bottle in the region of 12,000 bottles an hour—an annual output of beer simply too difficult for any small brewery to produce, often meaning they must outsource the process to a larger contract-brewer, making it difficult to enforce their high standards. This is not problem for AB Inbev, who can simply export beer to China bottled under American standards, or invest in mega-brewing facilities that can bottle over 200,000 units an hour without breaking a sweat. It’s hard for independent brewer to compete in volume, marketing, and on a whole host of other metrics.

Another reported practice of AB Inbev is to offer lucrative deals to bars, clubs, and restaurants to stock only their products. For bars running on small margins, such offers, it is claimed, are too good to turn down; once again the independent brewer is squeezed.

When he first arrived in China, Michael Jordan, Boxing Cat’s master brewer, was met at the airport by a gaggle of young basketball fans, who became distraught to meet a burly, softly-spoken beer brewer from Spokane, Washington, rather than a six-foot-six former Chicago Bulls megastar. Jordan was at Boxing Cat for several years before the buy-out, and is defensive about the sale.

“It is a tough situation. Any brewer who is really a brewer just wants to focus on making great beer. End of story,” he says. “The ownership causes different emotions from different reasons. What I have seen so far is a desire to grow craft beer in China and there are more resources now, than if we were to do it all ourselves…so it is maybe allowing us to push aside some barriers; that maybe there is that advantage.”

The Qingdao Festival is celebrated from Aug 4 to 27 at various venues throughout the coastal city (VCG)

“We are hiring local people, all that stuff. I guess it is a global company that has their headquarters elsewhere, so that takes away that whole local perception.”

Many independent brewers are adamant that once AB Inbev get their hands on a brewery, it can no longer be considered “craft.” According to the American Brewer’s Association, if a company produces more than 6 million barrels a year, or is more than 25-percent owned by a non-craft brewer, it cannot be considered craft (Boxing Cat obviously fails the latter test, which is also endorsed by the Craft Beer Association of China). But the definition seems self-serving: Six million barrels is a huge amount when the US only produces about 200 million a year.

“Goose Island’s not brewed in Chicago. Boxing Cat no longer meets the definition of American craft beer. But they still call it craft beer here. It’s not craft…It’s a lie,” Setzer insists. “[When Zx] were trying to make some sort of a gesture to us, [their behavior] was so abhorrent and so against everything that we suffered…that the temptation was not, ‘Oh, do we take the money or not?’”

“The temptation was to make a bigger scene about it, and invite the scrutiny of one of the largest distributors in China, someone who has massive influence over the future regulation of my own industry [and] straight-up has thugs on the street. Do I invite that kind of scrutiny? Do I make a big deal out of it?”

Given that only a month ago, Setzer took the microphone before a large crowd of Beijing beer drinkers and announced “F*ck [Zx] for trying to take my moment,” this seems a moot point. Whether customers feel as strongly as Setzer is not, though. Most are concerned with the simple, beautiful act of getting drunk; it is less likely they care who prepares their poison.

Yet there will always be a market for purists, or those who seek the more bizarre concoctions (Chinese beer infused with bacon, peanut butter and jelly, and Sichuan peppercorn all exist, as do baijiu beers). “Beer is the language of humans,” rhapsodizes Yorke. “It’s something that can be shared by people of any background…it the unifying, it’s the…well, whatever.”

Crafty Conglomerates is a story from our issue, “Vital Signs.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the App Store.