Despite a building boom, Chinese theme parks struggle to provide a fun experience to visitors

“Business should pick up next month, when children start their summer holidays…” The camel-keeper repeats this like a mantra as he surveys the nearly empty Egyptian exhibit at Beijing’s World Park on a Sunday in June.

Meanwhile, “I’m so bored that I’m about to fall asleep,” he complains. Indeed, even the camel beside him appears ready to nod off as she waits in her sand pit, droopy-eyed, for visitors to pose for photos at 20 RMB a pop.

Its collection of miniaturized world landmarks may seem kitsch and outdated to today’s well-traveled visitors, but Beijing’s oldest theme park has seen better days. The World Park’s 1993 opening attracted a respectable 20,000 visitors on the first day. It was a time when, according to Window to the Capital, a Beijing government news portal, “‘travel’ wasn’t in the vocabulary of ordinary Chinese, and ‘the world’ was someplace out of reach.”

It wasn’t just travel that was an alien concept in the 1990s, though—so was fun itself, claims Li Yong’an, the park’s chief mastermind. In his grandly titled essay “Without Reform and Opening Up, There Would Be No Beijing World Park,” published online in 2014, Li recalled a business trip to the US in the 80s, when his partners invited him out to Disneyland. “I didn’t know what Disneyland was. Only after getting there did I understand—it was someplace where you went to have fun.”

“That left a deep impression on me,” he writes. “[The US] had reached such a high standard of living that when their people finished work, they had fun.”

By comparison, the two-day weekend wasn’t standardized in China until 1995, and workers enjoyed just seven statutory holidays until 1999. Li, working as a civil servant in Beijing’s Fengtai district, had a hard time getting his superiors to approve his 1992 proposal to build a Disney-esque leisure park in Huaxiang, then a village outside the yet-to-be-built Fourth Ring Road. The capital already had two amusement parks, as well as the Grand View Garden, a tourist attraction made up of leftover sets from the 80s TV adaptation of the novel Dream of the Red Chamber.

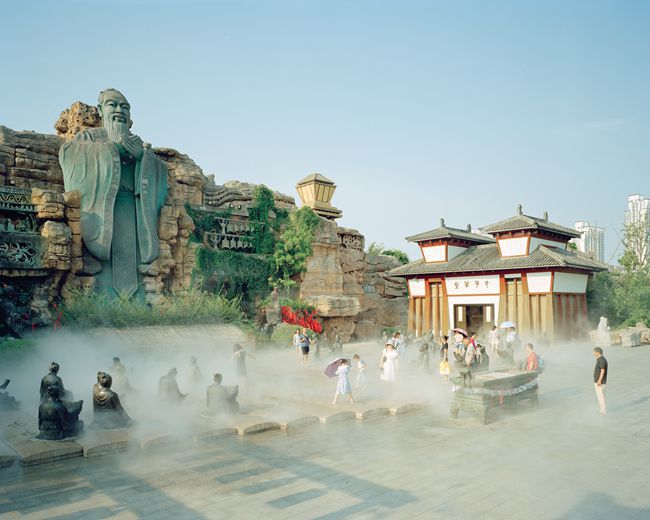

A 17-meter bronze Confucius statue is the centerpiece of Spring and Autumn Land

But building a manmade tourist attraction from scratch was unheard-of to Beijing officials at that time—much less one as ambitious as the World Park, which called for half a square kilometer of land, 150 million RMB in investment, and was expected to draw visitors from afar purely to be entertained.

On the other hand, compared to the government’s current paranoia about “Western influences” over domestic entertainment, architecture, and even place names, authorities in 1992 were surprisingly accepting of Li’s proposed theme, and even organized committees to study the architecture of Disneyland and the Maduroam “Miniature City” theme park in the Hague.

Although recent reforms had opened up China’s economy, few could afford—or were allowed—to go abroad in that era. “The World Park fulfilled people’s dreams,” Li writes, perhaps an unintended homage to Disney’s own slogan. One could take a train, car, or several transfers of bus to a small suburb of Beijing “to see the world.” Ticket revenue from the opening day was 830,000 RMB—around 8 million in today’s money, still impressive next to the 10.9 million RMB made in average daily ticket sales by the Shanghai Disney Resort in its first year of operation in 2016.

***

Today’s theme parks require a far higher outlay to build: 1.5 to 5 billion RMB and dozens of square kilometers of land, government officials say. There are now over 400 theme parks in China, estimates Shanghai Jiaotong University’s Institute of Theme Parks (ITP), although tourism officials put the total that have been built in the last 30 years as high as 2,500, including zoos, botanical gardens, science parks, and film lots. Each province has 20 parks on average, with some having 50; some cities alone boast as many as 10.

Few, however, turn a profit. Indeed, around 70 percent operate at a loss, with another 20 percent just managing to balance the books, according to domestic research firm Zhiyan; 80 percent may have gone out of business in the last decade. Construction in the last decade has been positively frenzied: 100 theme parks were built in 2012 alone, with dozens more expected to be completed by 2020. It’s a far cry from the tentative risk assessments that preceded Beijing’s World Park.

Live animals and dance performances are often found in theme parks

By 2020, China is also predicted to be the world’s biggest market for theme parks. Yet the expected industry victors are international brands, such as Disney and Universal Studios, via the Shanghai Disney Resort and Beijing’s under-construction Universal Resort, slated to be the world’s biggest. Consulting firm Colliers International declared last year that the industry was entering its “third era”—characterized by experienced global brands and international IP. Shanghai’s Disney Resort has already become China’s premier theme park in just three years of operation, welcoming 11 million tourists last year, though Zhuhai’s Chimelong Ocean World has recently caught up at 10 million.

“There may be 10 or 20 good parks in China,” goes the generous estimate of ITP director Gu Laifeng. The rest, uninspired clones, “are not just copies, but ugly and boring copies; stupid, too. I can’t even stand to look at them,” Gu says. “In terms of management, planning, creativity, and technology, they have a long way to catch up.”

Shandong’s Europark offers a Disney-like theme at a third of the price—Image courtesy of Shandong Provincial Department of Culture and Tourism (Europark)

There’s disagreement on what exactly went wrong, but the industry’s wild ride has already irked the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). Its 2018 statement, “Standardizing the Nation’s Theme Park Development,” identified “real estate orientation” as well as “unclear concepts, blind construction, plagiarism, and low-end duplication” as the major woes of Chinese parks.

While theme parks in countries like the US tend to be controlled by entertainment companies, China’s biggest park brands—Chimelong, Fantawild, and Overseas Chinese Town (Happy Valley)—are owned by conglomerates specializing in hospitality and resorts, technology, and property development, respectively (a fourth contender, commercial property developer Wanda Group, all but exited the industry in 2017 after a disastrous foray into movie parks).

In between, there are plenty of small-time developers and billionaires looking for new ways to turn ripe land into commercial property, hotels, resorts, or even mines. Theme parks have proved an unexpectedly useful pretext in the last decade. “You can’t just build condos anymore—the government wants to do things that are more value-added,” a business development consultant, who worked on theme park projects from 2011 to 2015, told TWOC on condition of anonymity.

Changzhou’s Dinosaur Land has expanded many times its original size

For anxious local governments, “a theme park is a perfect marriage of a lot of things,” the consultant adds. “It’s a really big landmark to put a small town on the map, it’s a good jobs-generator both during construction and during operation, and it generates tourism and tax revenue.”

Nowhere is this logic more evident than in Changzhou, Jiangsu province. The city of 1.4 million is described by its own tourism bureau as having “no famous rivers and mountains or historical landmarks,” surrounded by better-known destinations such as Suzhou, Nanjing, and Shanghai. In 1997, Shen Bo, a young civil servant and Jurassic Park fan, was tasked with attracting visitors to this unenviable spot. He came up with China Dinosaur Park, a resort built on reclaimed rice paddies outside of town.

This was followed by the development of the history-themed Yancheng Spring and Autumn Amusement Land in 2010, boasting an awe-inspiring 17-meter bronze Confucius—though the sage, like dinosaurs, was not native to the region.

Now calling itself China’s “theme park capital,” Changzhou’s roster of amusements has expanded to include the World of Warcraft-themed CC Joyland and Daoism-focused Oriental Salt Lake Resort, both more than an hour’s drive from the city. Salt Lake Resort is planned to cover a whopping 27.8 square kilometers. Joyland, meanwhile, unashamedly violates several international IPs including Starcraft, the Fantastic Beasts franchise, Doraemon, and even the Universal logo.

The original Dinosaur Land is now surrounded by malls, apartment complexes, a cinema, and a hot-spring resort. It is in the heart of the “new Central Business District” to which Changzhou relocated its government and much of its population last year. (Both Dinosaur Land and the Changzhou Tourism Bureau refused TWOC’s requests for comment.)

These are impressive testaments to the surprising role that theme parks have played in developing China’s hinterland—but not exactly endorsements on how fun they are to visit. “This is a classic example of real estate logic,” scoffs Jeffrey Woo, president of Sanderson China, the Shanghai-based division of an Australian creative consultancy that has worked on projects such as the Huayi Brothers’ Movie World in Suzhou and Kunming’s Colorful Paradise.

The government encourages theme parks to develop Chinese themes

“If you need to rely on a theme park to bring people and business into the area, that means your location is already a problem,” says Woo. (Even some Changzhou natives turn their noses up at local attractions. “I’d only take my son to Shanghai’s Disney, or abroad; only the best for us,” a local, surnamed Li, tells TWOC outside of Dinosaur Land.)

Instead of building in areas with the economic base to support a major tourist attraction, says Woo, inexperienced developers and officials have inverted the model. “Even if you manage to bring 10 million people to your park, where are they going to stay? How do they get there? What do they eat?” he fumes. “Theme parks are not something that helps you urbanize; they’re things that can be built only once you’ve urbanized.”

Then there are hundreds of parks that never actually get built—TWOC’s anonymous consultant estimates that, for every project that breaks ground, there might be dozens that are shelved after the land rights are signed over. “[The developers] want to show the government a beautiful master plan, feasibility studies, a 3D model, and all these rides…and they’re going to wait until the officials that approve it move on or step down, then throw up condos [instead], maybe add a little ‘cultural center,’” he alleges, noting that none of the theme park projects he was involved in over four years ever got past conceptualization stage.

Instead, developers rely on sales of property to realize their investment. “That’s the hustle—even if they do intend to build [a theme park], they’re often building solely for the purpose of realizing value on the apartment and condo sales in the vicinity,” the consultant says.

In turn, property sales become even more crucial to developers when their haphazardly built parks fail to turn a profit. “From the financial perspective, it’s a very nice collaboration, but I saw so many examples where the land was just ruined,” says the ITP’s Gu. A lack of attention and experience is also why issues such as crowd control, mechanical failures, safety hazards, and even fatal accidents are reported every holiday period in Chinese parks. “These are all problems created by humans—because they haven’t put enough thought into it,” Gu says.

Gu’s institute now runs a doctoral program for upper managers and staff of Chinese theme parks, covering every eventuality from communicating with ride designers to crowd-control to picking a catering service. It also crunches annual rankings of China’s best theme parks using public votes and data from travel apps like Ctrip and Lvmama, factoring in considerations like the entertainment value of a park’s live shows, or the tastiness and value of the food on site. “How can a real estate boss understand what’s enjoyable to tourists?” he asks.

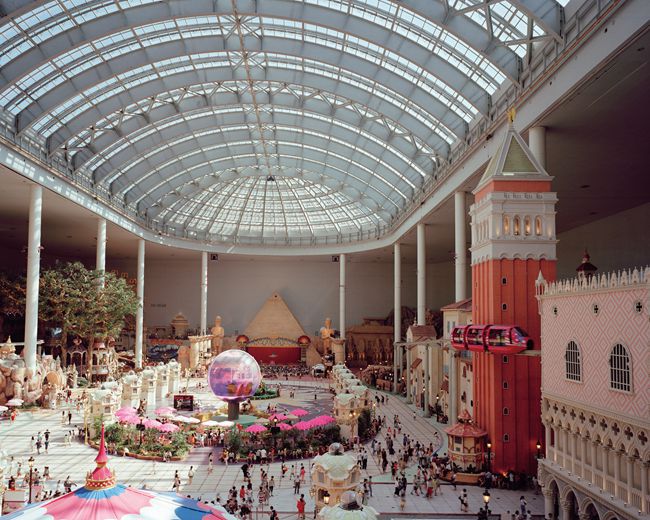

Romon U-Park in Ningbo, Zhejiang, is one of the largest indoor theme parks in the world

Indeed, many visitors complain that there’s often little to justify the high ticket prices, which Chinese parks, lacking merchandising or profitable IP, must rely on to generate revenue. “It’s just a lot of rides,” one overheated visitor, who declined to give his name, complains to TWOC while struggling to find shade in an all-concrete “ocean theme park” in Qinhuangdao, Hebei province. He’d gotten his 140 RMB entry fee waived, as he had connections to the military. “If I’d paid for this, I’d be so disappointed right now.”

***

“No one sets out to build a bad theme park,” says Sanderson China’s Woo, diplomatically.

“I wouldn’t say developers build them only to sell condos, either. But if you cut a corner here, and cut a corner there, you end up not doing good business after you open, and then you stop making an effort,” he says.

The government has already promised to tackle a number of issues in the theme park sector, including stricter controls over approving “mega-scale parks,” defined as those more than six square kilometers in size and 1.5 billion RMB (218.5 million USD) in investment, as part of a broader effort to prevent local governments from taking on heavy debt to fuel construction. Surrounding residential and property developments will also have to be approved separately from the park itself.

But Woo says the challenges “are too big to have a single answer. They’re related to the industry’s ecosystem, and further up, the development stage of the national economy, and further than that, a problem with Chinese [consumers] themselves.”

Disney’s arrival has brought to the fore the need for parks to develop an IP of their own—not only to allay plagiarism accusations, but as a business model. “Everyone realized, apparently that’s how you can build a park,” Woo says. “You cannot survive anymore with rides that only offer a physical experience, but you need to work in a story to tie everything together, to offer an emotional experience, and give it a direction and soul.”

“Having a theme is also useful in terms of developing multimedia advertising, and developing related products like merchandise and movies,” Woo explains. Indeed, Changzhou’s Shen Bo had already identified this problem in the early years of Dinosaur Land, and optimistically tried to correct it by developing a dino-themed animation series in 2007.

Water-themed parks have become popular in recent years

However, he admitted that it was always going to be uphill work. “Disney first had characters like Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck, then movies that spread these characters into people’s hearts…and then duplicated these characters and sceneries and emotions in physical reality,” he told a Nanjing newspaper in 2015. “In China…we build the park first, then create the characters and content, and then try to promote them—it’s like a tree without roots.”

Similarly, neighboring Joyland has been trying to prevent potential lawsuits by developing its own fantasy-themed video game as the basis of future rides. This is perhaps an even bigger struggle, given the content restrictions that stymie domestic game distribution in China. The NDRC, meanwhile, has been encouraging parks to adopt more overtly Chinese themes, a strategy already pursued by Changzhou’s Spring and Autumn Land—which has a Confucius robot that answers questions, a haunted house reinterpreted with the Spring and Autumn period’s “Five Warlords,” and a virtual reality ride through a historical battle (embellished with zombies and vampires).

Yet this is a hazardous strategy in its own right. In 2018, a People’s Daily editorial lambasted history-themed parks for offering inaccurate, overly commercialized, or shallow interpretations of ancient luminaries and traditions. “Though we may look on with displeasure…most visitors just think that it’s enough for a place built for fun to be fun,” the writer sniffed.

Perhaps, though, it’s exactly this sense of innocent fun that Chinese parks have lost since the days when Li Yong’an returned, wonder-struck, from his trip to Disneyland. It was with the sense of rediscovering this feeling that Shanghai-based photographer Chen Ronghui, an amusement park aficionado, began traveling around the Yangtze Delta region in 2015 to capture the varying styles of fun offered by the local parks.

The photos were collected in a series titled “Runaway World,” which Chen says partly represents the feeling of grandeur and hubris in China’s thousands of theme park developments, but also the earthier feelings of giddy excitement and thrill they bring to visitors. “They provide you with this sense of escape,” Chen tells TWOC. “There’s this spinning motion, a mentality of being unbridled. Say you’re a programmer in real life—but when you’re in a theme park, you’re simply enjoying yourself in the moment.”

Chen believes most of the parks’ challenges, like poor quality and lack of originality, can be met as China’s middle class continues to grow, urbanize, and demand more creative forms of fun. “I grew up in a small town, and never saw an amusement park until I moved to the city for college,” he says.

“Having friends take me to theme parks, marine parks, and all these different places you can go with the sole intention of being a consumer and enjoying yourself—that’s an experience you only have when you move to the city. I want to capture moments that express how Chinese people find enjoyment in the present.”

3 Strange Theme Parks

Dwarf Empire – Kunming, Yunnan

Located within the World Eco Garden of Butterflies, this 14-million USD park is staffed by over 100 little people, all under 130 cm tall, who live in mushroom houses and perform variety shows. This brainchild of real estate tycoon Chen Mingjing sounds like the kitschiest form of exploitation, but the staff claim they are happy to have employment and a home.

Minsk World – Shenzhen, Guangdong

Though it’s closed at the moment (with plans to re-open in Nantong, Jiangsu), this was once the premier place in China to enjoy a slice of Soviet naval life on a decommissioned aircraft carrier. When doors opened in 2000, Minsk World featured a variety of old military gear—including old helicopters, Howitzers and MiG fighter jets—as well as a stage show and simulator deep inside the hull.

New Old Summer Palace – various locations

Though the original in Beijing was burned down by Anglo-French forces in 1860, there are two to-scale replicas of the imperial residence in Zhuhai, Guangdong, and Hengdian, Zhejiang. The latter, a whopping 30 billion RMB reconstruction, is still unfinished. There is also a miniature version at Shenzhen’s Splendid China park.—Han Rubo (韩儒博) and Hatty Liu

Wild Rides is a story from our issue, “Wild Rides.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the App Store.