Japanese “two-dimensional” culture appeals to a new generation of Chinese consumers

Waking up at 7 each morning, Zhao Jingyu opens the video streaming platform Bilibili to check for updates to his favorite Japanese anime Fatima. Later, when he starts to nod off on the subway, he might listen to the show’s theme tunes through his headphones to stay awake and find the courage to face another routine day at work.

Japanese “two dimensional” culture, or erciyuan (二次元), has lost none of its cachet for Chinese youngsters more than 40 years after the debut of Astro Boy, the first animated show imported to China from Japan. In Chinese, erciyuan is an umbrella term for a variety of visual products imported from Japan, including animation, comics, games, and novels (ACGN), as well as offshoot merchandise like action figures and costumes.

Consumers of erciyuan products in China are expected to rocket to 403 million in 2021 from 160 million in 2015, according to iiMedia Research, a Guangzhou-based consumer behavior analysis firm. A study from 2018 by Jiguang, a Shenzhen-based data analysis company, shows that 64.3 percent of Chinese erciyuan consumers are under 25 years old, and erciyuan culture is growing the fastest in this demographic.

The golden age of erciyuan began during the Japanese recession of the 1980s and 90s, when the country’s economy transitioned from manufacturing to the culture industry. In her book Anime from Akira to Princess Mononoke: Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation, scholar Susan J. Napier suggests that many features of influential works from this period, from the 1985 film Nausicaä to the 1997 series Neon Genesis Evangelion, feature apocalyptic settings “suggesting a society with profound anxieties about the future.”

For Zhao, though, the idealistic setting and inspiring music of his favorite shows are an enticing contrast from his real life. “By getting deep into erciyuan anime, I feel like I can get away from the real 3D world, which is full of obstacles from work and family,” the 22-year-old tells TWOC.

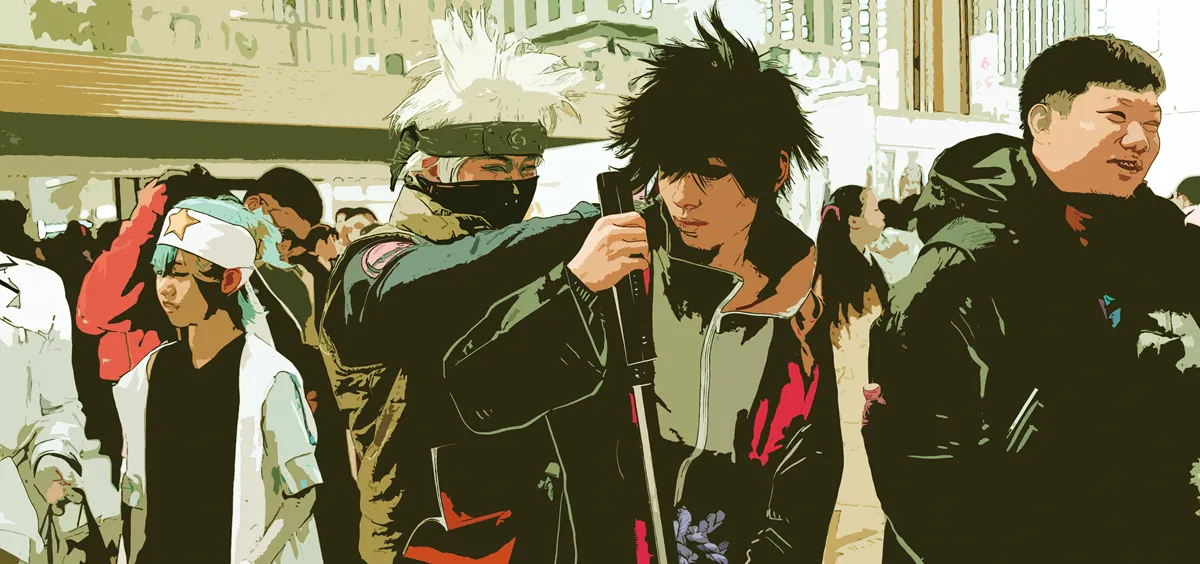

Anime conventions are where erciyuan fans can cosplay, buy merchandise, and meet fellow enthusiasts

Zhao usually watches anime for no less than three hours each day. He has been a fan since age 7, when, like many children of his generation, he watched dubbed versions of anime on Chinese television. This interest even led him to start studying Japanese at age 16 and becoming a Japanese teacher.

Erciyuan culture developed in China in the 1980s and 90s, with imports of animated shows like Astro Boy and Doraemon. It has since grown due to rising income and streaming technology, which allow viewers to access new anime directly from Japan without waiting for the Chinese import and dub.

In 2007, erciyuan video platform AcFun was developed, supporting a “bullet screen” function where viewers can input live comments that will flash across the screen as the show plays. In 2009, the ever-popular Bilibili launched, counting over 90 million monthly average users by 2018.

As the biggest platform for erciyuan content today, Bilibili offers exclusive rights to stream the latest anime from Japan and live broadcasts of anime conventions. Members can access exclusive videos and get a personalized profile picture drawn in anime style, which user Du Linhao says has helped him make connections in the erciyuan community. “I look at others’ profile pictures, and if it’s a similar style to mine, I add them as friends,” Du, an undergraduate student from Huazhong University of Science and Technology, tells TWOC.

Not everyone has such positive experiences, though. Zhao says others have stereotyped him as a “homebody” (宅) or its equivalent in Japanese, otaku. “My parents don’t like me to spend time on watching anime,” says Zhao, who hides the extent of his hobby from his family. “Rather than watch cute female characters, they try to persuade me to go out for dates with girls. They hope for me to be more extroverted.”

According to data firm AliData, China has a population of 50 million “empty-nest youths” aged 20 to 29 as of 2017. This term, popularized by a China Youth Daily report in 2017, refers to youngsters who live alone in big metropolises away from their families, have few friends in the city, and are usually the only child of their parents.

Zhao believes the stereotypes are unfair, pointing out that he meets plenty of people from around the country at cosplay conventions, where attendees dress up as characters from their favorite shows and buy ACGN-related merchandise. “Many Chinese teenagers [who enjoy erciyuan] still socialize with others at conventions, and they are well-balanced between work and life,” he argues.

The China International Cartoon and Game Expo is now in its 15th year

Examples of extreme Japanese otaku “marrying” erciyuan characters using AI technology reinforce negative impressions of the fandom, but Du believes this stereotype confuses cause and effect. “Poor social skills may lead otaku to become addicted to idealized anime, but erciyuan movies and culture are just a platform for letting out emotions and finding friends with common interests,” he says.

Zhao agrees. “I think phenomenon like a late marriage or staying at home all day long are not proper labels for erciyuan lovers,” he reckons. “They’re more like social problems caused by multiple factors, from heavy pressure at work to the increasing number of Chinese students pursing higher-level studies.”

For now, this hobby remains affordable for Du and other erciyuan lovers he knows, who are mostly students, as he pays just 98 RMB for a one-year membership on Bilibili, and spends up to 200 RMB occasionally on dolls related to his favorite show, Naruto. According to iiResearch, nearly 60 percent of erciyuan lovers will pay for their hobbies, but 40 percent of them will just pay “occasionally” for a specific item related to their favorite programs, or if they can get a discount.

For products like tickets for cosplay conventions and costumes, the cost still deters the majority of Chinese erciyuan fans, with iiResearch finding less than 3 percent of respondents participating in cosplay, showing vast room for the market to grow and provide better content to inspire consumer loyalty.

For 23-year-old Li Jiankai, his hobby deserves its price. Though the English teacher in Langfang, Hebei province, earns just 5,000 RMB each month, he recently spent 500 RMB buying a costume from the Chinese mobile game Onmyoji to attend a cosplay convention in Shijiazhuang.

Li also buys Gintama anime dolls for 50 to several hundreds of yuan once in a while. In Guilin, a 21-year-old female college student interviewed by Guilin Daily said she has spent over 30,000 RMB on costumes, dolls, and anime conventions.

“Erciyuan-related products could increase in value as some are limited collections,” Li muses to TWOC, justifying his purchases as an investment.

However, Li is still mostly driven to pay by sheer love of erciyuan media. And though the vast majority of that media remains Japanese, Chinese fans are beginning to embrace domestic products. Li’s favorite game, Onmyoji, was developed by Beijing-based company NetEase with music by Japanese composer Shigeru Umebayashi and character design inspired by Chinese ink-wash painting. It became a hit when it was released in 2016, and ranks eighth in revenue among all Chinese games.

Domestic filmmakers have also produced a few high-grossing animations in recent years, including Wukong, Big Fish and Begonia, and Ne Zha—the latter grossed in over 5 billion RMB at the box office in 2019. During the “Double Twelve” online shopping event on December 12, 2018, a skirt licensed by domestic anime Feirenzai, priced at over 4,000 RMB, sold out within 20 minutes.

Zhao is optimistic about the future of his hobby. “Lots of Japanese studios are outsourcing design work to China, and Chinese companies are investing in Japanese animation…it all indicates the beginning of widespread acceptance of erciyuan in China.”

He hopes though, that his hobby doesn’t grow too mainstream. “I think most people embrace [erciyuan] because they love it,” he says. “As a non-mainstream culture, it’d be ideal if we can keep it within a somewhat small group.”

All images from VCG

Love in 2D is a story from our issue, “Rural Rising.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the App Store.