Chinese cities scramble to deal with Hubei travelers stranded due to coronavirus, amid reports of discrimination

Xiao Dan would have laughed at the cliché at any other time: Mother and child, New Year’s Eve, and no room at the inn.

The 40-year-old from Wuhan and her teenage son had been in Beijing to attend a four-day family relations seminar. Originally planning to return to Wuhan on January 23, Xiao was instead stranded in the capital when her hometown became quarantined in a bid to contain the novel coronavirus outbreak—and was then told she could no longer stay at her hotel due to the building being “closed for maintenance.”

“It took police intervention to finally settle everything,” Xiao tells TWOC, explaining that public security officers had stumbled upon her situation during checks on Wuhan visitors in the neighborhood. “They said the hotel wasn’t allowed to shut down, and told us to stay put until [February] 1 [when the prescribed 14-day incubation period ends].”

Having already gotten a clean bill of health from the hospital, Xiao thinks she has exhausted her options. “I just have one wish: They don’t have to host us for free, but at least don’t drive us out.”

An estimated 5 million Wuhan residents had already left the city by January 23, when the Hubei city’s new Epidemic Control and Prevention Center suspended all air and ground transportation out of the city, leading inbound airlines and trains also to cancel scheduled stops in the Hubei provincial capital.

While many are students and workers who have simply returned to their hometowns for the lunar new year, others are tourists, business travelers, and short-term visitors like Xiao who call Wuhan their home, and now find themselves unable to return.

The issue of what to do with this “floating population” from the epicenter of the outbreak—which also now includes other residents of Hubei province, where all but one prefectural-level administrative region has been locked down at the time of writing—proved an unprecedented challenge for cities around China in the confused early days after the travel restrictions were imposed.

Frightened by rumors that many Wuhanese already presenting symptoms of infection had “fled” the city prior to the shutdown, residents of other Chinese cities have been reporting people and vehicles from Hubei in their neighborhood to the police. On January 27, a Shanghai-bound China Southern Airlines flight was delayed for five hours in Nagoya, Japan, after other Chinese travelers refused to board with passengers from Hubei.

In several provinces, including Fujian, Guangdong, and Hunan, the names, addresses, phone numbers, and national identification numbers of those arriving from Wuhan were published online by local residential committees, leading many to report getting harassed by strangers by phone and WeChat. Travelers have also reported getting turned away by hotels and apartment owners, or having their vehicles vandalized, due to the tell-tale Hubei identification on their ID cards and license plates.

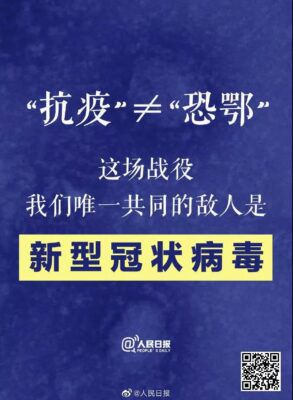

“Combating disease” is not equal to “fear of Hubei,” exhorts this notice published by the party-run People’s Daily on Monday (People’s Daily WeChat account)

At a press conference on January 28, Ma Guoqiang, deputy secretary of the Hubei provincial party committee, stated he believed discriminatory actions against travelers from the province were “extreme individual cases.” “I believe the vast majority of places will treat Hubei people kindly,” Ma said. At the time of writing, 21 cities have designated hotels where visitors from Hubei may stay.

However, not every city is offering these lodgings free of charge, and some emergency measures have had unintended consequences. In a January 29 report by Renwu magazine, a Hubei traveler said his family received free room and board at designated hotels in Zhanjiang, Guangdong province. Earlier, however, they had seen other listed hotels in Haikou, Hainan province, that appeared to be closed to business.

Two travelers in two other provinces, who declined to be formally interviewed for TWOC’s story, shared that they had to pay at the designated hotels—one was at first assigned by local authorities to a luxury resort whose rates she could not afford, and was not permitted to look for a cheaper alternative off the list.

Xiao says her hotel began providing her and her son with food free of charge as of January 26, saving them around 200 RMB per day in expenses. Police also intervened when the hotel tried to raise the price of their room to 600 RMB per night, almost double their original rate. “When our quarantine is up, we plan to leave here, but I don’t know what to do after that,” she tells TWOC. “[Staying in hotels] is not a long-term option for our finances.”

The situation is especially dire for those living on the economic margins: Du Hao, from a city in southeastern Hubei, had come to Beijing to work as a food delivery driver on January 10. On January 22, after hearing that the virus could be transmitted between humans, he switched to what he felt was a safer job with a property management company.

Just two days later, however, on the lunar new year’s eve, Du was ordered to move out of his new company’s dormitories. “They were concerned that having someone from Hubei on staff was going to affect their business,” he tells TWOC. “I tried sleeping in the park until it got too cold, so I went to the 24-hour [ATM] kiosk at the bank, but tripped the security alarm…[a guard] told me I couldn’t stay.”

Unable to afford a hotel because he only had 80 RMB on him, Du called the police, who took him to the hospital for a check-up and then to the city district’s homeless shelter, where he now gets meals, lodging, and twice daily temperature checks for free. “I think I’m the only person from Hubei here, but I’m not sure, because I feel too embarrassed to talk to others,” he says.

Du, who has displayed no symptoms, and has been in Beijing far longer than the virus’s believed incubation period, is not sure when he can leave the shelter, or of his next steps after that. “[The police] advised me to stay here until the controversy dies down.” Earlier in the week, he tried to leave to find Sun Tao, a Beijing property owner who posted a widely shared message on WeChat offering free room and board to stranded Hubei travelers.

Sun tells TWOC he was moved to make this offer by reading about discrimination against Hubei visitors online. “I think people need to stop treating them like enemies. “You can’t say you love the country if you don’t love the people—that’s fake patriotism,” he argues.

Since he posted his message, though, Sun has received messages from strangers accusing him of endangering his community and “not being a real Beijinger.” This was followed by a visit from the police. “They asked if there were any Wuhanese living here, and asked me to be careful,” he tells TWOC. “They recommended that I take down my message, because providing room and board is the job of the government.”

At the time of writing, Beijing has not published a list of hotels for stranded travelers, though some residential communities, such as the one where Xiao is staying, appear to be making individual arrangements with hotels. “I can understand why the hotel might [feel scared],” says Xiao. “I’ve already ordered 20 masks to give to their staff, which is all I can do for them.”

“Do you have any solutions for me?” she asks TWOC, and sighs.

Update: As of January 31, 2020, the Hubei provincial party committee is “working on a plan” to bring Hubei travelers home from other parts of China.

Names have been changed to protect the identity of those interviewed.

Cover Image from VCG