How ancient Chinese battled moths, mold, and moisture to keep their manuscripts safe

According to the National Bureau of Statistics, China has published 11 billion books in 2021. That’s nearly eight new books for every Chinese citizen. In ancient times, however, books were far more exclusive, reserved for the small proportion of the population who were literate and could afford them.

In fact, one curious netizen has done the math: During the Northern Song dynasty (960 – 1127), when merchants were beginning to flourish and book prices were relatively low, the official price for one volume of a book was 100 wen (1 wen was roughly 0.7 yuan today). The Confucian classic Mencius (《孟子》), a philosophical text of 14 volumes read nationwide, would have cost 1,400 wen, approximately 980 yuan today.

Since books were so valuable, and took so much effort to produce before the advent of modern printing techniques, they had to last a long time. But before paper, protecting written works from mold, moths, and disease required a host of innovative maintenance methods.

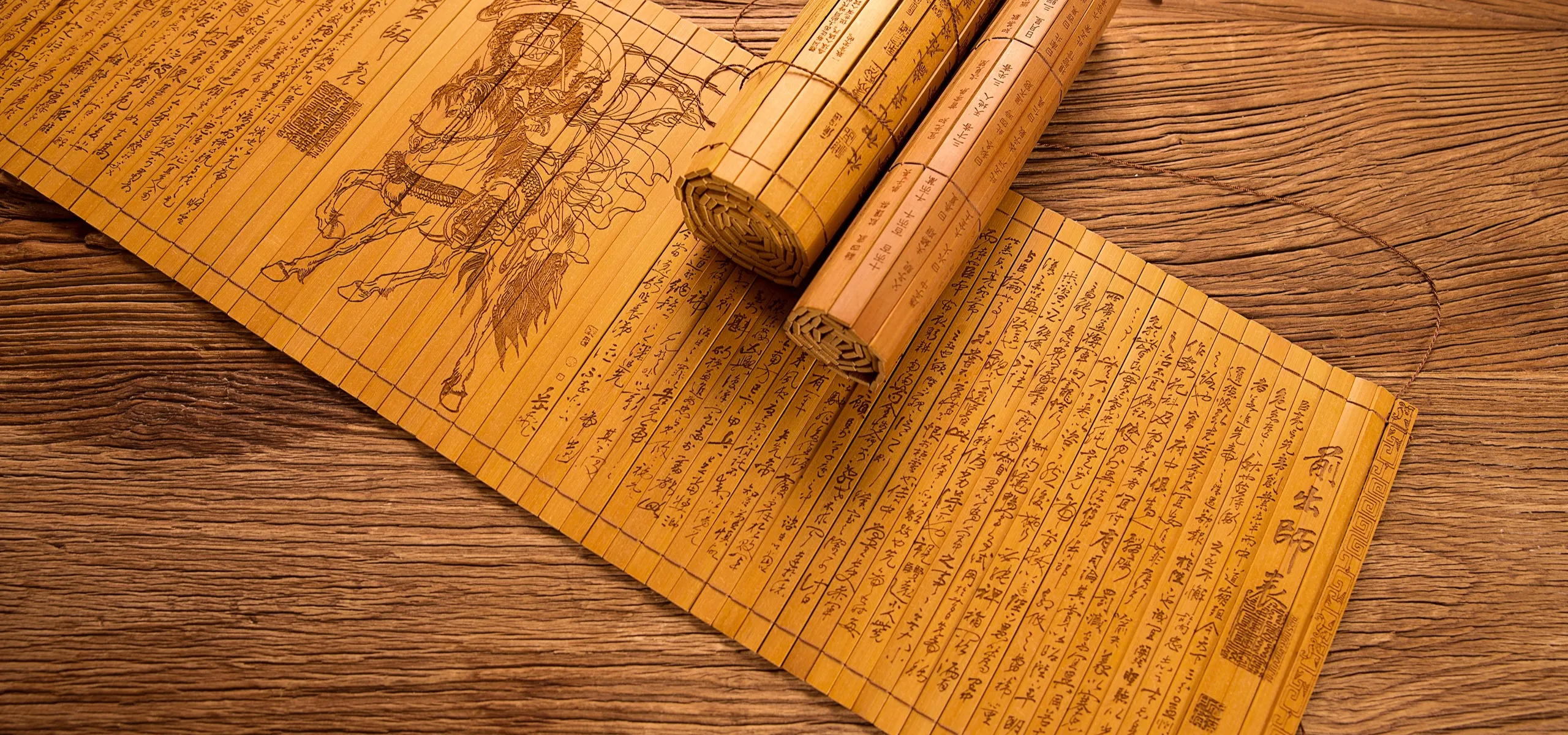

Prior to the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), when eunuch Cai Lun (蔡伦) improved paper-making technology and promoted it across the empire, books were mostly written in ink upon rows of bamboo slips. Though the bamboo was firm and durable, it required protection from moisture and parasites.

Protecting bamboo-strip books involved 杀青 (shāqīng, literally “kill the green”) a procedure that involved drying the bamboo strips before writing on them. Han-dynasty scholar Liu Xiang (刘向) recorded the practice in his encyclopedia The Subject Catalog (《别录》): “Since the fresh bamboo contains moisture, it is easily eroded or eaten by worms. Anyone who makes writing slips of bamboo should dry them on the fire first.” The term 杀青 is now used to refer to the completion of a book manuscript.