Young curators talk to TWOC about transcending stereotypes through art

In the past year, the mountainous Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture has been declared a “final battleground” in the national campaign against poverty. Its newly built roads were traversed daily by dozens of journalists from around the country, reporting inspirational news of “cliff villagers” moving down the mountain and into new homes.

Yet for people growing up in this region of southwestern Sichuan province, the mountains are not a political buzzword, but simply home. Last year, Moxi Zishi (ꂽꌋꋩꏂ in Yi script), Mose Yiluo (ꂽꌋꀀꆧ), and Shama Shizhe (ꎭꂵꏁꎆ), who also goes by Ma Jianlan, founded the platform “Echo of Liangshan (ꌩꁐꇤꉘꉼꃚꐝꄧꀕ)” in their hometown of Xichang to promote cultural exchange within the region, and between the region and the outside world. They are joined by Guoji Yixin (ꈢꐞꒉꑟ) and Jihu Wuzi (Hu Yongmei) (ꐛꃛꃴꊪ) as core organizers.

Until February 5, the curatorial team will show the self-titled exhibition “Echo of Liangshan” in Beijing’s Laii Gallery, bringing together 100 pieces of photography, painting, prints, sound documentary, and experimental video depicting Liangshan from the eyes of 47 ordinary people in the region, “instead of more children with dirty faces and runny noses” common in mainstream portrayals of the region, says Yiluo.

Curators Yiluo, Shizhe, and Wuzi speak to TWOC about growing up in an era of rapid changes in Liangshan, and what they hope art can do in the face of it. “Art is not only about a feeling of beauty, but an act of imagination and cognition,” says Shizhe. “Although we are from Liangshan and belong to the Yi nationality, we are fundamentally all human beings, and these interactions can form a bridge.”

None of the exhibiting artists are professionals—some are students, homestay hosts, police officers, designers, and poets—and neither are the curators: Yiluo is a master’s student in international development studies, Shizhe is a lawyer, and Wuzi works in finance. All three are women born in the 1990s who have wandered far from their hometowns geographically, but not in spirit.

“In the end, we hope and bless the land that bears and nurtures us,” says Wuzi, “and it is still abundant and full of hope.”

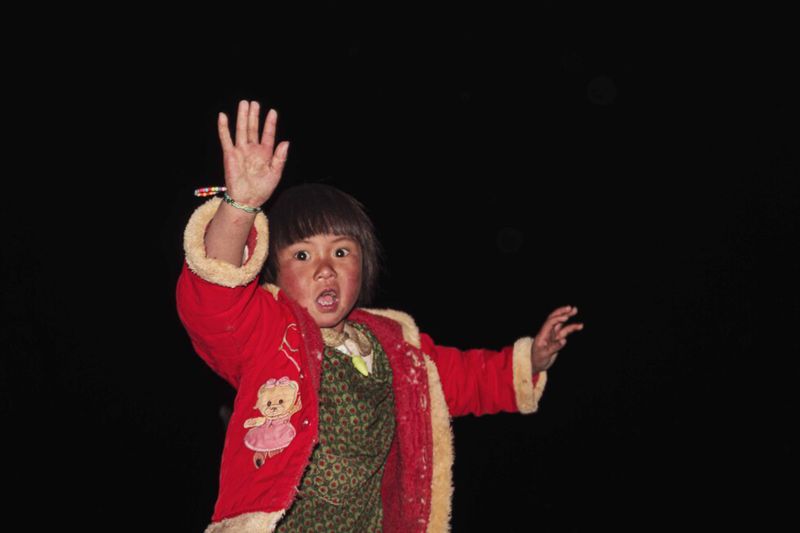

A’geng Zhili, “My Little Sister”

How did the platform and the exhibition come about?

Shizhe: We had always hoped there could be a platform in Liangshan for young people like us, or people who are interested in Liangshan’s culture, to share and exchange ideas. We usually study and work all around the country, but when we returned to our hometowns during the pandemic, we didn’t have such a platform, so we wondered if we could build one. The platform Echo of Liangshan was officially established in 2020.

We held our first event in April in Xichang, a salon on the theme of marriage and gender. After that, we held a vintage bazaar, book club, movie screenings, and even a costume party—our line-up continued to grow and evolve. Especially for those in our hometown who have the same cultural background as us, but don’t have resources to access more cultures, we hope to give them the right to choose how they should live and think.

Then, when some of us gathered back in Beijing again, we hoped we could bring Echo of Liangshan here, so that even those outside of Liangshan can feel the changes occurring there, and give us a platform to tell our stories to the outside world.

Riddle Jiang, “A Yi Woman”

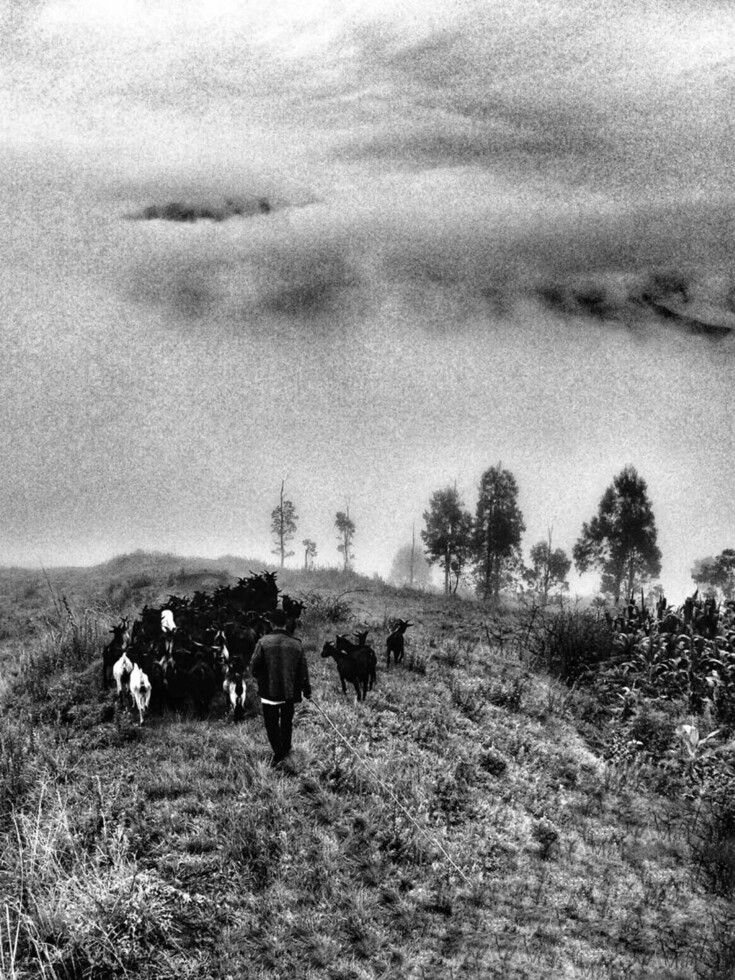

Jibi Ziga, “Return from the Pasture”

Yiluo: I think our current role can be expressed in two words. One is “bridge.” On the one hand, we are connected to Liangshan; on the other, we are connected to people in the outside world who are interested in Liangshan. We can transmit voices in both directions.

Another role is “catalyst”—we were very pleased to see that there were some 2,000 young people who attended our cultural events; some have even started their own. A variety of local youth activities have sprung up one after another. We have set in motion a process for local youth to see more possibilities, and to pursue beauty.

Wuzi: The idea of amplifying the voice of Liangshan has been budding in each of our hearts for many years. We hope to give the people of Liangshan a window through which to understand the world; at the same time, it also allows people outside to understand Liangshan more authentically.

We don’t want to beautify Liangshan, or to package it for viewers. We hope that the outside world will no longer understand this land from a perspective of “otherness,” but to truly understand what is happening on this land and to the people on it.

Ageng Zhili, “‘Too Cool’ Kid”

What narratives are you seeking to complicate with this exhibition?

Yiluo: In organizing this exhibition, our curatorial team opened an online submission portal and received 695 works from 47 contributors. We were met with works that were surprising and moving, set in mountains and plains as well as cities. Due to the many backgrounds represented [among our contributors], from poets to police officers, these works show their various living spaces, and reflect their perspectives and dreams. Together they form archipelagos, or constellations—emerging from the eyes of scattered individuals yet connected by a regional thread.

Shizhe: Public attention on Liangshan has increased in recent years, yet many of the labels given to us are related to poverty or drugs. Although these phenomena objectively exist, I feel that poverty is not only material; we are rich in spiritual life. There are many Yi nationalities living in Liangshan, as well as Han people, and there are many interesting collisions of ideas. In the past few years, more and more friends around me have become determined to express our version of self—to give voice to Liangshan’s diversity, not just images of drugs or poverty.

Wuzi: The public exposure of Liangshan in recent years is an opportunity as well as a challenge. It doubtlessly brings in external resources that drive economic growth and employment. While the well-being of a place is inseparable from the economy, faith and culture are equally indispensable. We need to look at things dialectically.

If a culture is to maintain its vitality, it needs to have some traditional adherents. These people may be the folk artists, craftsmen, elders, and wise people scattered deep in the mountains and fields of Liangshan. But it also needs young people like us—or even younger people—who have perhaps received a better education, and can look at the outside world from a different perspective, in addition to our understandings of our own culture. The culture will be presented more vigorously and youthfully, in different forms, in a “cooler” way. The ideas we uphold are the same, but the way we do things is different. We need to respect and support both.

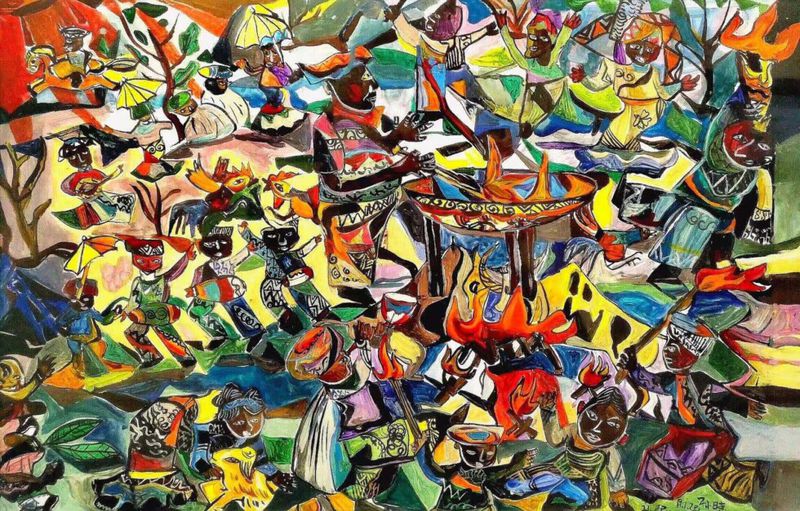

Sun Xiao, “Liangshan, My Homeland: Torch Festival of the Yi Peoples”

How has Liangshan shaped your perspectives of yourself and your work?

Wuzi: I think we have all gone through four stages regarding self-identity. The first stage is the long process of growing up in Liangshan. When we lived on the land, we lived and breathed traditional ways of thinking, and we didn’t think about our culture from a bird’s-eye view.

The second stage is when we passed the college entrance exam, moved from Liangshan to the most modern cities in China, and entered good universities. Jianlan and I came to Beijing at 18 years old, and Yiluo went to Shanghai. We actually felt a loss at this time—we may have been eager to use our nationality as a label in order to find a sense of security in a competitive and unfamiliar environment.

And then we enter the third stage, developing in our respective fields, we have built contact with and knowledge from all over the country, and even the world. We want to prove that I am good because of my professional ability, not because I am a minority.

We are now in the fourth stage. Having lived and worked outside for many years, we begin more consciously looking at our identity again. We embrace new attitudes and thoughts, and integrate it into our own ethnic group, our hometown, and our families. At this stage, we may not be trying to shed the label of Yi ethnicity; but as a member of it, how can we embrace this land again? How can we give back to it through our own abilities, to nourish and love it in a better way?

Yiluo: Even as we enter new stages, we will always maintain our love for this land, and do our best to nourish and love it. Meimei [Wuzi] once told me of a quote by a Tibetan writer, Alai, who said something like: “I went into the depths of the world, and found that my origin is also my destination.” This sentence captures our journeys and is the thread running through our lives.

Shizhe: As Yiluo said, even as our origin may be our destination, it doesn’t mean we must physically return—Liangshan is always part of our spirit. As the new generation of Yi people, we have more opportunities to seek further horizons, but we shouldn’t be limited by our current imaginations. We should look to our future and its countless manifestations.

Ageng Zhili, Playing the Yueqin

Images courtesy of Echo of Liangshan and Laii Gallery, cover image is “Liangshan, My Homeland: Yi People’s Beauty Contest” by Sun Xiao

Mountain Echoes is a story from our issue, “You and AI.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the App Store.