Chinese-American architect’s bold designs spoke to a complicated relationship with his birth country

The death of Chinese-born architect Ieoh Ming Pei (贝聿铭) has been greeted with a flood of tributes and retrospectives from his adopted country of America all across the world to China, where his modernist approach helped bring an end to three decades of Stalinist architecture.

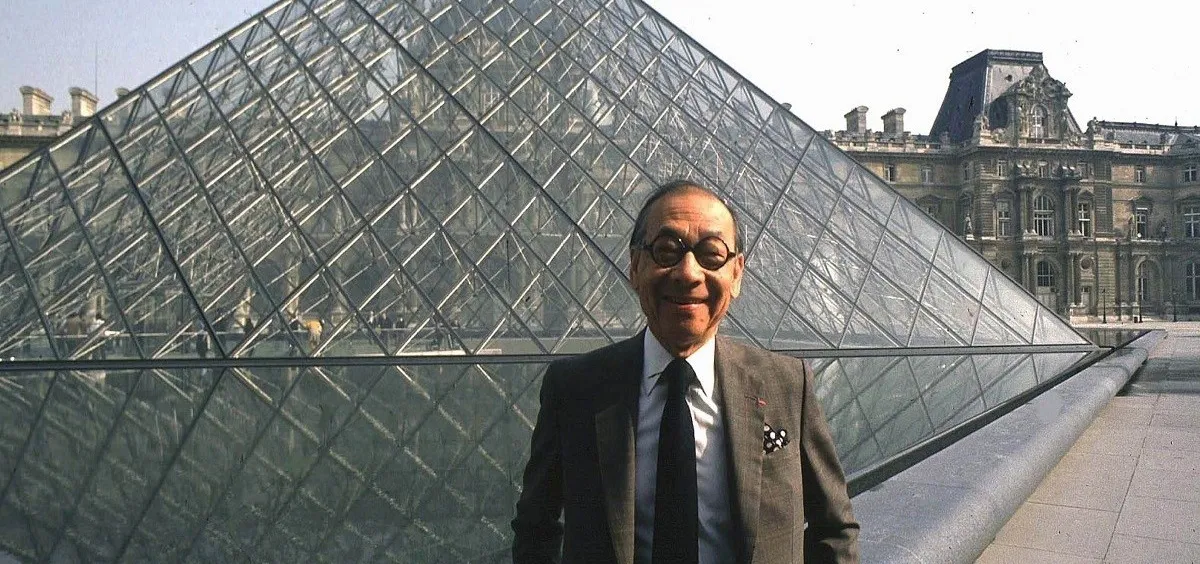

I. M. Pei, who died on May 16, aged 102, was probably best known for the 71-foot glass pyramid serving as the entrance of Paris’s Louvre Museum. The pyramid, which bathed the underground galleries with natural light, was initially lambasted by critics after completion in 1989, when Pei received “angry glances in the streets” after being selected by then-French President Francois Mitterand to deliver the project.

It is now an “icon” revered alongside the Mona Lisa, said Louvre director Jean-Luc Martinez. The controversy was typical of an architect who faced down adversity from an early age.

Born in Guangzhou in 1917 to a prominent Suzhou family, Pei grew up in Suzhou and Shanghai before traveling to the US in 1935 to study at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard. He had planned to return to China—his thesis projects included a rural recreation center, and a Modern Cubist art museum surrounded with gardens intended for Shanghai—but was prevented by chaos, war, and revolution.

Pei would end up living in New York for the rest of his life, but early ideas, such as his museum, would bear fruit in later designs he would compose after visiting his homeland. “I returned to China to visit family in the 1970s, nearly 40 after I departed the country,” Pei wrote in 2004. “I feel that China is in my blood no matter where I live. China is my root.”

In New York, Pei started out designing low-income housing and office building before establishing his own firm in Manhattan in 1955, now a US citizen. The beneficiary of a political decision to entice talented Chinese to stay in the US as citizens, rather than returning to become Cold War rivals, Pei’s decision to stay would eventually provide inspire for generations of immigrants about the heights of success that could be achieved as a Chinese in America.

After meeting Jacqueline Kennedy in 1964, Pei was picked to design the John F. Kennedy Memorial Library in Boston, and his stateside star was in the ascendant. Pei first returned to Beijing with a delegation of American architects in 1974, at the tail end of the Cultural Revolution, where he was asked to design a high-rise hotel in the capital.

He was reluctant to undermine the city’s historic character, much of which had been lost during the Mao years. returned again to build the the Fragrant Hills (Xiangshan) Hotel in the city’s wooded outskirts in 1983.

Pei’s first design in China proved a tortuous, ultimately disappointing project (via Wikimedia)

Though necessarily muted in design—he described dealing with the Chinese system as “most tortuous thing I’ve ever done”—the modest Pei was always ready to help teach local architects how to draw from their own roots by fusing traditional elements with modern concepts. His firm was later able to adapt the ideas behind the Fragrant Hills Hotel on a much grander scale with the Suzhou Museum in Pei’s ancestral hometown, which broke ground in 2002.

The building, which featured a steel-and-glass façade and white stucco erected around an array of classical Suzhou-style gardens, was the subject of a PBS documentary, Building China Modern. It was one of Pei’s last official commissions, though he technically only retired after the 1990 completion of the 70-story Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong, which was Asia’s tallest building at the time (his father had been one of the bank’s founders). It was a typical Pei design, with its base resembling bamboo shoots to symbolize China’s resurgence, and the triangular quadrants anchoring the tower in a bold and futurist look.

As many mourned his passing on Weibo, China’s foreign ministry released a statement that Pei had “made important contributions to the mutual understanding between the Chinese and American people and the exchange of eastern and western cultures for a long time.”

Cover image from VCG