Five rare traditional Chinese instruments with thousands of years of history

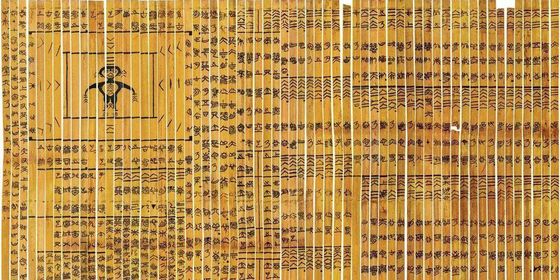

In 433 BCE, the late Marquis Yi of the minor fiefdom of Zeng was laid to rest on a sandstone hill in the north of what would become Hubei province. This obscure chief would lie there undisturbed for the next 2,400 years, until a team of hydraulics engineers discovered his tomb in 1978—along with over 1,000 intricate pieces of ancient musical instruments that he was buried with, the largest and best preserved collection yet to be found in China.

Reigning during China’s chaotic Warring States period (475 — 221 BCE), the music-loving marquis would have been well-schooled in the “six arts” of the junzi (君子), or Confucian gentleman: rites, music, archery, charioteering, literature, and mathematics. Music ranked only second to rites in the list, and ancient Confucian culture was also known as 礼乐文明, or “civilization of rites and music.” Kings and emperors employed “music officials” (乐官) who were in charge of providing music for court entertainments and religious rites—one well-known official musician of the Lu state, Shi Xiang (师襄), was a teacher of Confucius.

As a result of this long music-making history, China now boasts many uncommon, even unique musical instruments, some of which are still popular today:

Xun 埙

Xun dating back to the Shang dynasty (c. 1600 – 1046 BCE) found in Henan province (VCG)

Not to be confused with the ocarina (陶笛), the xun may be one of the oldest musical instruments in human history. It has been discovered in 6,000-year-old archeological sites of the Hongshan Culture, and is believed to have evolved from rocks used by Neolithic peoples to hunt. The xun is an egg-shaped instrument usually made out of clay, with finger holes cut out and a hole across the top which the player blows into. When played, it makes a muted, chilling, and slightly mournful sound.

Excerpt: “Song of Chu” by Zhao Liangshan

Sheng 笙

Modern sheng are typically made from brass, though bamboo was traditionally used (Nikolaj Potanin/flickr)

The sheng is a reed instrument composed of many vertical pipes of different lengths. It is polyphonic, which means it can play multiple notes simultaneously. The player blows into a mouthpiece and manipulates the finger holes on the side of the pipes. Another instrument with a long history, the sheng was first mentioned in the Book of Songs, a collection of poetry dating back to the 7th century BCE, and a version of it was discovered in the tomb of the Marquis Yi of Zeng.

Excerpt: “Colorful Clouds” by Zhao Junyi

Suona 唢呐

A suona player in Miyun, Beijing (VCG)

Loud, brassy, and not for the faint of heart, the suona, or double-reed horn, is a favorite annoyance at Chinese weddings and funerals. Believed to have originated in Persia, the suona was ideal for outdoor and community celebrations due to its bright and penetrating timbre, and it is an important part of folk music traditions in northern China.

Perhaps due to these grassroots associations, the suona has fallen out of fashion lately: In 2017, Shandong TV reported that several villages in Caoxian county, Heze, have banned folk bands (响器班, usually consisting of suona, sheng, gongs, drums, and other folk instruments) in order to curb lavish weddings and funerals, one of many rural regions to have done so. Suona players complained they were being threatened with fines and getting their instruments confiscated, and expressed worry about the future of their art.

Excerpt: “Hundred Birds Welcome the Phoenix” by Noble Band

Chimes 编钟

A porcelain model of bianzhong and player unearthed from a Han dynasty tomb (202 BCE – 220 CE) (Augusthaiho / CC BY-SA)

Made up of multiple bronze bells hung on a wooden frame, the chimes, or bianzhong, was traditionally played during religious rites, before war, and when the emperor held court. The bells may be of any number or size—the biggest existing collection, now housed in the Hubei Museum, was also discovered in the tomb of the Marquis Yi and consists of 65 total pieces. These 2,400-year-old chimes have been played just once in the modern day, at an exclusive concert in Beijing’s Zhongnanhai compound to commemorate the 35th anniversary of the founding of the PRC in 1984; afterward, the bianzhong were returned to the museum, and a replica was made that’s still occasionally played during important state functions, such as the return of Hong Kong in 1997.

Excerpt: “Bamboo Sonnet” by Unknown Artist

Hulusi 葫芦丝

A street musician plays the hulusi in Wuxi, Jiangsu province (VCG)

Indigenous to several ethnic minority groups in Yunnan province, including the Dai, the hulusi, or “gourd flute,” is made up of three reed pipes attached to a gourd. The player blows into the top of the gourd, which forms a natural resonating chamber producing a rich, smooth, and sensitive melody.

Excerpt: “Shepherd’s Song” by Tan Yanjian